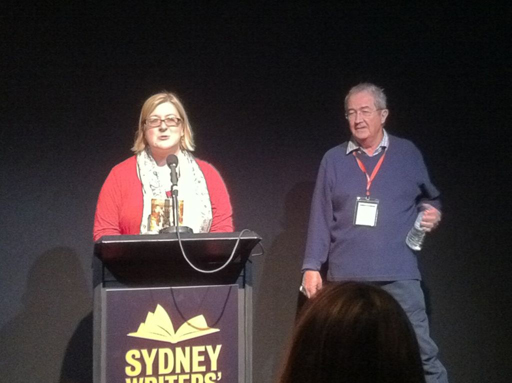

Last year, I attended an “In Conversation” between author (and my friend and colleague) Libby Gleeson and Geoff Williams at the University of Sydney. Libby is an Adjunct Professor in the School of Education and Social Work, and the In Conversation canvassed her creative process as a writer of picture books and longer fiction for children and young adults. The session was extremely interesting for anyone interested in getting an insight into how a particular writer works. I also found it reassuring, as someone who teaches a course in writing children’s and young adult fiction, that many of the things I discuss with my students were reinforced by this highly acclaimed author.

So it got me thinking that I probably would do well to spend more time talking the specifics of craft with my writer friends, and if I’m going to do that, then why not publish them on the blog. Old Misrule suffers a bit from the cobwebs of lost inspiration from time to time, and this might also be a good way to freshen things up a bit (thus also the new WordPress site!).

So here is the first in an occasional series about writing. The title of this blog post comes from the epigraph to the novel The Shadow Girl, by John Larkin, the subject of this first interview. The quote goes as follows:

Nothing exists but you. And you are but a thought—a vagrant thought, a useless thought, a homeless thought, wandering forlorn among the empty eternities.

Mark Twain

Do I need a name for this occasional series? I love, love, love that show Inside the Actor’s Studio, and I am hoping to do something a bit like that here—including the Pivot Questionnaire that they do at the end (except maybe without the ‘favourite curse word’ to keep it PG). Shall we call it Inside the Writer’s Garrett? (I’ve made a temporary category with that name so people can search for it as I add more interviews to the blog, and I’ll add it to the post title as well if we agree to go with it.) Or is that just too silly! Anyway, if you have any ideas, let me know—and if you have any questions for me or the author, you can leave them in the comments and we’ll respond. (Hhmmm, I just realised I didn’t make that a condition of the interview, so I hope John doesn’t mind me dobbing him in like that! Also, he hasn’t actually done the questionnaire at time of posting, so I’ll add it in later, when he’s had a chance to respond.)

The other thing to say is this: Here Be Spoilers. I’m not going to spend ages providing plot summaries or explaining details of narrative choices beyond the basics, but there will almost certainly be spoilers in any of these interviews, so Caveat lector. (Yeah, I know that’s almost certainly wrong.)

Nota Bene: Please note that these interviews will not be promotional vehicles for specific titles. I will not necessarily be tying them to a particular book, although this first interview, with John Larkin, is primarily about his most recent novel The Shadow Girl, and I do indeed hope you all go and by and read it. But this is not intended a promotional opportunity, and frankly, I’d rather any writers or publishers reading this didn’t approach me for an interview, as a.) I am not sure how many of how often I’ll have time to do them, and b.) I really only want to do them if I’m inspired, rather than feeling obligated. (For instance, I’m reading page proofs of a new novel at the moment by one of my favourite Australian YA authors, and this writer has chosen a different narrative voice from their previous books, and I am quite keen to talk to them about this choice and the challenges involved in such a dramatic shift.) And similarly, I only want to talk to people if they are excited about talking about process, so if you do feel a compulsion to offer yourself up, make sure that you pitch what aspect of writing you’re exploring yourself and are keen to talk about and share. And I’ll think about it. 😉

So, onto the first interview.

John Larkin has been writing books for children and younger teenagers for about as

John Larkin

long as I’ve been writing about them—around twenty years, is my guess, and he’s published, according to his website, more than 23 books. (You can read more of his biography at the site as well.) And although our paths must have circled each other’s many times, I don’t believe I actually met John until I was asked to launch his collection of short stories, Bite Me! (I have a photo of us at the launch somewhere, but I can’t find it.) I also reviewed John’s memoir, Larkin’ About in Ireland, for Viewpoint. (And if I can find the file for that, I’ll post it too!)

John’s books have been largely characterised by their humour, which is something we discuss in the interview, and by and large by a fairly straightforward narrative style and structure. He went quiet for a few years, as far as publishing went, and when I saw him at the launch of The Shadow Girl, my first comment to him was, Hey, it’s been a long time between drinks!

And I know I said I wasn’t going to do plot summaries, but it probably will help if I give a bit of background to The Shadow Girl. The book was inspired by a homeless Year 8 girl John met at a western Sydney high school he was at as a visiting author. He didn’t get very much information about this girl, other than she more or less lived on the trains, but her story, sketchy as it was, stayed with him and became the inspiration for this novel.

And because The Shadow Girl is such a departure for John, in every way—tone, content, structure, even the age of the intended readership—I was keen to talk to him about how his writing had developed over the years and some of the choices he made for this novel. I started by explaining that I wanted to talk about…

_____________________________

…process and craft rather than content, although content sometimes comes into it as well.

Well, they’re intertwined

Because I am interested in some of the plot choices you made, because I think they were risky, but I think you pulled them off…

Well, that’s nice to know!

So I wanted to start off talking about structure, because it is the one thing I have the most difficulty understanding—well, not understanding. I’m really interested in it. I did my masters in narrative theory* and I’m really interested in the mechanics of it, but I find it the most difficult one to work with students on. Largely because most of them don’t have a draft they’re working on, so I have to talk in really broad terms about the “big picture” elements of structure. So I’m interested in learning more about and hopefully communicating about it better. So tell me how you came to having the dual narrative.

How that came about… like a lot of stories, you let it percolate for a few years. Structurally, I originally started it in the third person, and I always intended to write it in the third person, past tense. Because that’s mostly what longer narratives use, it’s the general go-to narrative voice. I’d written pretty much the first chapter and I felt distant from the main character. And I didn’t want to reveal what she looked like, I didn’t want to reveal her name, so I thought the only way I can really do that is looking out through her eyes. And how could I make it even more immediate—by writing in first person, present tense. But that brought up a raft of new problems, because I wanted to move backwards and forwards through time, and the way that came to me to do that was to have me interview her. She’d had this life-threatening event, circumstances, and she was now looking to tell her story, and that’s how I came up with the idea of the café chats. The idea was I would interview her, do exactly what you’re doing now, have the transcripts typed and up and have them published. The other point of that was then have her be a less than reliable narrator. Occasionally she was going to tell me lies, the big one towards the end, where she let us have the denouement of the story when she was lying. I questioned her, believing she was lying, and she was convincing enough that I believed her, but then she felt guilty and came back and told me what really happened. So it was kind of fun to probe that kind of narrative voice and also to have a narrator who was economical with the truth.

But then that’s layered too, because the story is not written by her, it’s written by the fictional you.

Correct. And it also gave it a heightened sense of realism, because many people believe that those transcripts are real.

Really. Are you getting that kind of response from people?

Yeah.

Why—what do you think it is? This happens from time to time with fiction. It happened with Gary Crew’s Strange Objects, it happened with Tony Eaton’s Into White Silence…

And Life of Pi, as well.

Really? What do you think it is, this impulse that readers have to want it to be true? That blog you sent me—she wondered if the transcripts were true. That would never have even been a question for me.

I suppose in more recent years there’s been an increasing blurring of the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction and this is taking that to the next level, I suppose. People are writing non-fiction that’s turning out to be fiction. So I’m writing what is clearly fiction and people are then reading it as non-fiction. Because it does say “inspired by a true story”. And I was clear that I wanted inspired rather than based on a true story, because I think “inspired” clearly lets us know that this is a work of fiction. But there are certain post-modern techniques that authors will use to try and have the reader think, this is real, isn’t it? This is true.

Were you consciously…

Oh yeah. I was consciously saying, let’s blur these boundaries a bit. Yes, I’m telling a story—and I tell some real—there’s some really clearly obvious works of fiction in the book, and that’s for me to remind the reader that you are reading a work of fiction. Sometimes that might be stretching credulity to breaking point, but I think it’s also important to let the reader know, don’t forget, yes it’s based on someone’s life but only very loosely.

So talk to me about the fictional you.

The fictional me was simply that was me put in that café situation. I asked the questions I wanted to reader to want to ask. If I told every aspect of the story that I wanted tot write, that book would be 1000 pages long. Having the fictional me in the café interviewing her certainly cut it down to a manageable 400-or so pages.

So it allowed you to leap certain things…

It allowed me to leap backwards and forwards through time. And what questions would the reader be asking at this point? So I was able to have those things as questions rather than narrative moments, because it would have just gone on and on and on. It’s tempting to write a 1000 page novel, but how many of us got through A Suitable Boy? It’s a big commitment for a reader. So cutting it down was also to help the reader get through it.

But it’s not just a dual narrative, it’s a layered narrative. There’s a fictionalised you in there, there’s a fictionalised girl inspired by a real girl, and then the fictional you takes the real girl in the novel and tells her story using fictional techniques, narrative techniques. There were a couple of things that struck me. One thing that struck me—when I’m talking to my students, we talk a lot about finding voice, and about writing dialogue, and about how good, strong dialogue shouldn’t need a lot of tags, because we ought to know who’s speaking and all of those basic principles, but what you can’t always say to them, what you can’t ever teach them, is how to do it well. That’s just practice…

Practice, intuitive. And trying to reflect real dialogue as well.

Uh-huh. So how do you do that?

The conversations that take place are as real as the conversation you and I are having now. So it’s not as if I’m actually making things up. Those things really happened. And that might sound bizarre, but… At one point, I bring her here, to the Macquarie Centre. I don’t name it, but this is the mega-mall in the ivy belt. And she goes to a café, having just survived the encounter with her uncle. Now, she’s sitting in the coffee shop, and she wants to get a sandwich and a hot chocolate, and the waiter who comes along was supposed to be a dismissive, arrogant young man, who thinks she’s cute, wants to ask her out, and realises she’s so young, wants nothing to do with her. That’s how I wanted to write him. He didn’t come out like that. When he turned up, he started being nice to her. And I’m going, I didn’t expect you to say that at this point. And that’s where creativity lives. It’s almost as if the writer is along for the ride and all I’m doing is sort of mopping up, writing down what my characters say. And that’s where fiction truly lives. When I’m not even controlling what the characters are saying, this stuff is happening and I’m just taking notes.

But there other things you are conscious of, you make conscious choices and conscious decisions.

That’s more to do with structure. So each chapter I’ll have an idea, OK, where’s she going? She’s coming from here to here, and there are a few dot points along the way. The rest is creative—let it go.

Do you plan those dot points out in advance? Do you plan the whole shape of the action?

I have a shape for the entire book. I have the opening line, the closing line, and a kind of loose structural breakdown of what each chapter will do and a few dot points of what may happen along the way. Sometimes you’re taken off course.

Have you always written like that?

No. Sometimes I just have an opening line, a closing line, and I just go for it. This one, because it was such a big story, I felt I had to keep a bit of a tighter rein on it. Stick to the story plan, but still allowing some room for creativity to roam.

So coming back to voice. Those transcripts, the interviews—you don’t use tags, there’s not even a visual clue, you don’t use different typefaces for the different speakers.** And yet it’s always completely clear all the way through who’s speaking. Was that something you had to work at, or did you hear her voice so strongly…?

Just heard her voice so strongly. And if this is meant to be a true transcript, these are how they are typed up. And sometimes she would speak over two or three paragraphs, but you had to know it was her. Her voice was so string to me. And now that dialogue tags weren’t allowed—the convention (of transcripts), I just couldn’t do them, in those transcript chapters, but I had to make it quite clear who was speaking.

But you could have prefaced it with initials…

I thought of that, but the idea is, it’s a secretary, it’s a typist listening and writing down what’s she’s hearing and putting down a new paragraph where there’s a change of speaker or an obvious pause.

But then you had to take her voice and take her back a couple of years, so she’s younger in the narrative chapters, and channel it through your fictional author voice, and there is a definite difference in the transcripts and the other chapters.

Well, in the transcripts, she’s almost 18, when we first meet her in the actual story, she’s just turned 15, when we meet her in the house. But then he wants to go back further, so we meet her when she’s in Year 3. So she must be the same character and she must have a similar intellect, but she must of course be more naïve. And all I had to do was think of this girl, put her in a Year 3 school tunic, often visualising my own daughters, and she was there. And again, I’m just then writing down what she’s thinking. And she’s still feisty as a young girl, but she’s still naïve.

So, the “inspired by”. Did they give a lot of back story at the school?

Not a lot. Just enough to break my heart. I mean, how is she surviving? Not only surviving, she’s prospering. And she was so intelligent and so eloquent. And it broke my heart to see her in this situation. And they weren’t prepared to reveal a lot to me, because in some ways the teachers were a bit complicit in what she was doing, because they turned a little bit of a blind eye to her travelling the trains, but she felt safer on the trains than she had done in foster care. Because she’d been subject to a certain amount of—I don’t know how much abuse she’d gone through, but what was happening in her life made her self-reliant, so I wanted a girl who was very, very self-reliant.

So that brings me to what I was talking about before, about the risky plot choices.

Right! OK! Fire!

So you didn’t go down, perhaps, what might have been the expected route, with her family context and all the rest of it. It wasn’t just a case of an abusive family she might have escaped, or been thrown out of, but, a crime family. So why did you make that choice?

I wanted the bad guy to be quite layered. I don’t know how he comes across to the reader, but I wanted him to have aspects of kindness to him. I didn’t want a stereotypical mafia hit man.

But why have a criminal (family) at all?

It just spoke to me that way. And he’s only a small-time criminal. He’s not a major player. He wants to be bigger than what he is. For me, it just suited the character, that he had these shady deals happening around her, and it also spoke to the darkness of the corners of her life, that there’s things going on there, in her mother’s background, in her father’s background, in her aunt and uncle’s background, that you might call the dark shadows in the corner. I wanted not to completely reveal what was going on there, but I wanted to hint that this was a very shady man, but not quite as Tony Soprano as he wanted to be.

Because you could have gone down the “poor abused child”… and then I suppose, the risk in that direction is that it becomes the issue novel about…

That “it”. That thing. The abuse. The abuse becomes the thing. Whereas, for me, the potential abuse was just part of her story. I didn’t want this to be the poster book for an abused child, I wanted it to be the poster book for hope. That you can get out, that you can get help, and also that people are good. The people who are around her, the people she meets in a wider network, she’s wary of them, but they turn out to be good. And I think that in our experiences in life, I think the media is so negative, it focuses on the road crash of humanity, but if you look at your own encounters throughout each day, you’ll have nothing but really good encounters with people. I had a car accident recently. A woman hit me from behind. We became friends. And after that—I looked after her, made sure she wasn’t hurt, and then we spoke on the phone. There was no potential for road rage there from me, and in my experience, that’s humanity, it’s not this road crash. But because she’s experienced such bad stuff, and because she’s used to this train wreck of humanity, including the media, that once she gets out there and she realises that people are actually good… There are some bad people, and she encounters them, but mostly she’s surrounded by good people.

And people step in.

People step in, because people want to help. And I think that’s human nature. We do help people, and it does give us that squirt of serotonin, we do feel good when we help someone, and that’s what makes humanity wonderful, and I think humanity is wonderful. And it’s such negative perceptions we have of ourselves as a species, but I think humanity is good.

Now, when I saw you at the launch, and I said to you, it’s been a long time between drinks, John, and you said that you wanted to take your time over this book. Can you talk a little bit about that?

I think previously I’ve become very excited about certain projects, and I’d just find this quite comfortable voice—the voice of Spaghetti Legs, Pizza Features, Lasagne Brain, Goon Town, Growing Payne, we could keep going… and they were nice, little, funny novels that people read and laughed, and ah! Larkin’s funny, and—put it away. I feel I’d got to the stage of my career, for want of another word, where I really wanted to do something that meant something to someone, if only me. So whereas in the past I’d put bits of me into my books, I wanted to do something where I put all of me into it. Now, other times, I’d written books and I’d think, oh, that’s a good line, I’ll save it for that novel over there. So as I’m writing a novel I’m always thinking about what I’m going to do next. This one, I wasn’t thinking about what I was going to do next. Everything was going into this book. And that’s why I took a fairly long time to write it, but also, I wasn’t in any rush to get it out there. I wasn’t trying to beat some deadline to get it out before (say) CBC were coming up with their shortlist. I just said, this was the book I’m going to put everything into, it will get out when it’s ready. And that’s how I will work from now on.

I don’t mean this in a way that is critical of the previous work, because those books that you have just rattled all the titles off, are great examples of that kind of writing, but you have gone to another level with this.

And I was always being asked about that…

And it’s not that it’s more serious in content…

I know what you mean…

Which is sometimes an assumption that we make, that if it’s funny it’s not as substantial and that’s not true—and there’s plenty of humour in this as well…

Absolutely.

I don’t think you can write not funny.

That’s the thing. I knew that going in. But I had to pare it back a little bit, and I thought, there can be gags in here, and there can be huge moments of levity, but it’s always be tempered by what was happening in her life, which was tragic. So I suppose it was always finding the right story to tell, where that would take me to a new level. My former publishers, Mark Macleod and Lisa Heighton, were always saying, you need to go to the next level. I never knew what that meant, until I did this. Having written my Irish book, I thought that was the next level, because it was non-fiction, it was funny, and serious…

I reviewed that! For Viewpoint.

You did.

And do you know what I remember saying about it? That there were points at which I wanted you to go…

Deeper.

Yeah. That it was a little, you know, that you didn’t always have to finish with a joke.

And that’s probably been my writing. I suppose I’ve always—previously, the narrative has existed between the gags. This time, the humour is there to serve the narrative, not the other way round. And that’s what’s taken me to the next level, if I can use your phrase. The humour’s there to support the story, not the other way around.

The Shadow Girl, published by Random House Australia

_____________________________

John was featured on Radio National’s Life Matters in October 2011. You can listen to the program here.

* Feminist criticism, narrative theory and the fairy tale retellings of Donna Jo Napoli, actually.

** Dear Blogger hopes that Dear Reader has noted the nod to The Shadow Girl’s untagged transcript in this interview.

…