From misrule.com.au/s9y

Originally published Saturday March 6 2010

________________________________________

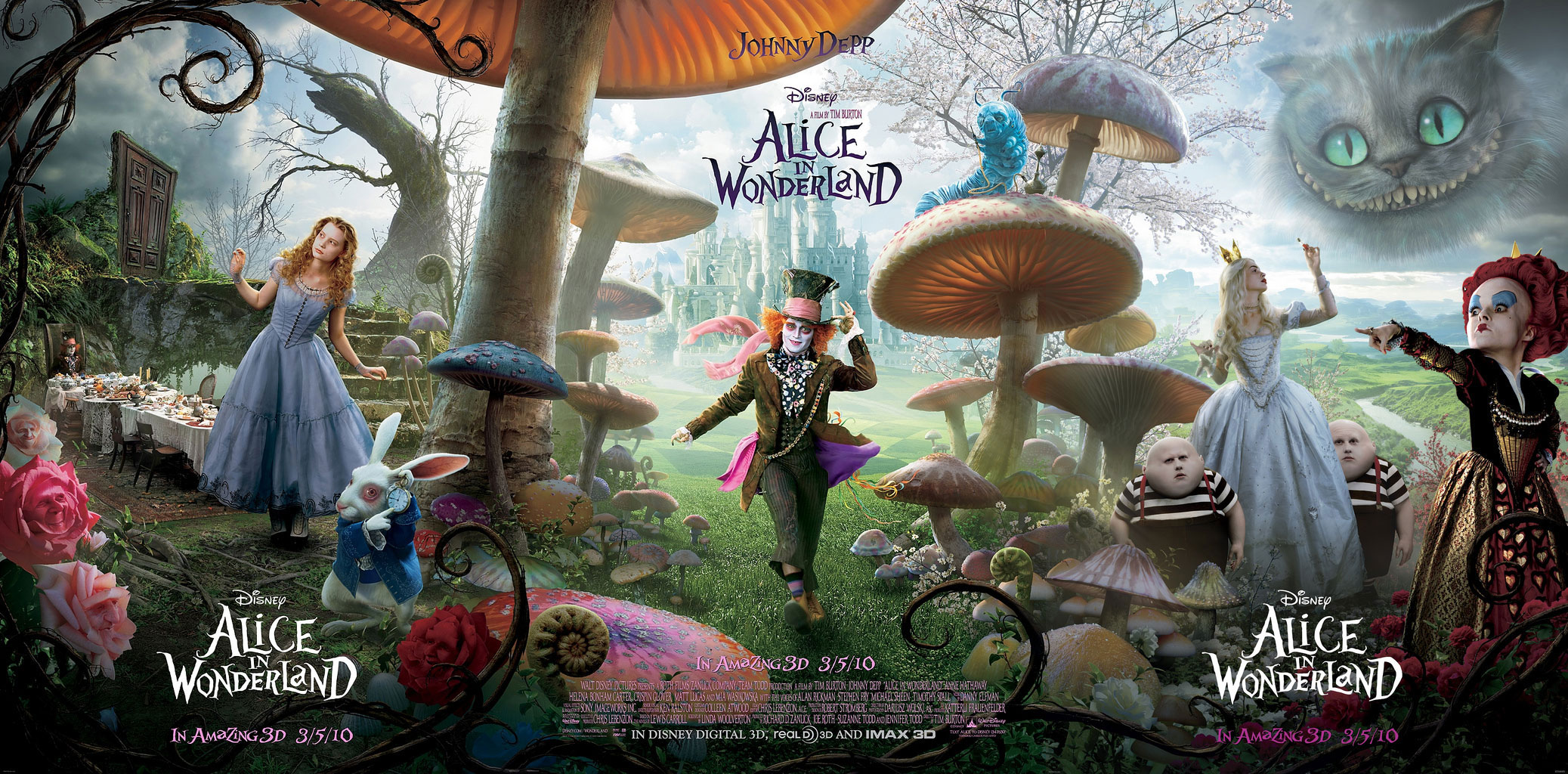

I went to see Alice in Wonderland last night.

As some of my readers will know, Alice is one of my favourite books. I have a smallish but nice collection of different editions of Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, as well as another small but interesting collection of Alice-abilia/-iana, whatever you call it. (China, characters in different media, including a set of Beanie Babies of the Disney cartoon versions of the characters, 1920s toys, etc etc. Also Carroll-iana—I’m sure I’m making these words up!—collections of his photographs, biographies and so on. I should photograph the collectins and post it for those interested.) I’m not unusual in that regard: Alice is held dear by many of my friends in the children’s book world, and I wouldn’t say I’m any more of a fan than many, and less than some. But I thought it was worth mentioning as I am about to discuss the film: Alice figures large in the history of my reading life, but I am by no means a purest when it comes to adaptations or interpretations. I’m always interested to see what artists see in the books, which is why my collection focuses on illustrated editions across the past nearly 100 years. I don’t think I’ve really seen a straight filmed version of the book that I love, but nor do any offend me mortally. (I just don’t watch the Disney cartoon one, makes life very simple!)

So there you are: my personal context for seeing the film.

I should also say that I am generally pretty open-minded about film adaptations of books. I guess I tend to view them as very different experiences, and I go to see a movie and hope it is a good movie in movie terms—I don’t expect to see the book replicated on screen. That said, I do think it’s possible to completely ruin a book, and that’s usually the case with movies “adaptations” when you see the film and think, why did they even bother to pretend that it was based on the book. Or adaptations which so egregiously misrepresent important elements of the book—such as the race of the main characters—that I get as outraged and upset as the next person. But if a film makes a fair stab at adhering to the emotional truths of the book and don’t play fast and loose with its politics, I am usually OK with it.

And having said all that, Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland is not, of course, an adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

I didn’t realise that when the first trailer teaser was “leaked” on the internet. I assumed it was going to be Burton’s vision of the book, but it’s not. Well, not exactly. Instead, as I was more or less relieved to discover, the film was to be set several years after Alice’s adventures in Wonderland, when she is 19, and apparently escaping an unwelcome marriage proposal. I have to say the sound of the engagement plot didn’t appeal much (and it turns out that it still doesn’t appeal, now I’ve seen the film, but more of that later), but I didn’t mind the idea of the movie being Alice’s return, especially given Hollywood’s penchant for adding years to a protagonist’s age for the sake of “audience appeal” (read: The Twilight Effect). What I mean is, if they were going to cast an adult actress, then for heaven’s sake don’t pretend she’s 10, or worse, update the book to match her age. So on that count, the “sequel” idea sort of appealed, and in any case, I was interested to see what Burton would do with this “Return to Wonderland” approach.

For me, what he did—and I know that comparisons are odious, and I actually generally really love Burton’s films, so forgive me—but for me, what he did was give us a bit of a mashup of Narnia (with the Red Queen stepping in for the White Witch via a slightly mean caricature of Elizabeth 1) and a NorthernLights/The Golden Compass Lyra-esque prophecy with a dash of BBC costume drama (I’d say Austen but it’s about 40 years too late…), all with a modernish feminist(ish) sensibility.

And I don’t mind any of that, really. It just kind of seems… beside the point. The frame is pretty silly. The lost father stuff works OK motivation-wise (as my friend Monica points out at Educating Alice, her blog which is, of course, named for Carroll’s heroine), but the engagement stuff is pretty silly. The potential fiance is so utterly repugnant, and why on Earth would his stuffy mother be so keen on the engagement if the family business has gone bung? We don’t know who Alice’s sister is until an utterly spurious scene in which Alice finds her brother-in-law kissing someone else in the hedges, which is, and remains, apropros of absolutely nuthin’, and is a very silly modern addition in any case. Simply put, the frame adds nothing thematically to the main story: it neither adequately reflects nor expands on the main themes of the film, and as such, is more or less pointless. I was, however, glad to see Lindsay Duncan and the sublime and under-utilised Frances De La Tour (although as Bonham Carter herself has pointed out, Burton makes no concessions to an actress’s vanities!).

Someone in the group I saw it with said she kept waiting for the actors who played characters in the frame scenes to pop up in Underland (which is apparently its real name, misheard by the child-Alice—I actually quite liked that innovation). Apart from two non-identical twins who were meant to echo Tweedledee and Teedledum, this doesn’t happen, and I’m glad of it. I think it’s a weak point of the film of The Wizard of OZ, having characters in OZ played by the same actors as Dorothy’s friends and family in Kansas, suggesting as it does that it was, after all, “just a dream”. (I’m sure this is original to the film, but I haven’t read the book since 197-gulp, so someone will have to remind me if I’m wrong.) I liked that W/underland is real and that Alice THOUGHT it was a dream, and I’m glad she gets to remember it at the end. (I did think, for a moment, though, that Dorothy’s red shoes might make an appearance… if you’ve seen the film, you may know the moment to which I refer.)

In fact there was quite a lot I did like about the film—Johnny Depp, who is always worth watching, makes a terrific Hatter, as expected (and what did everyone else think of the use of the raven and the writing-desk riddle as a sort of refrain between him and Alice?). Anne Hathaway as the faux-affected White Queen was very amusing (and I don’t think Wonderland is going to be all that better off under her rule rather than her sister’s, actually!). Alan Rickman’s sinuous voice for the Caterpillar was marvellous (although I am still a bit puzzled why so many of the characters got names—the Caterpillar is Absolom, amongst others, and I don’t geddit…) I was a bit disappointed in the Cheshire Cat (despite my eternal adoration for Stephen Fry), not sure why, and the poor White Rabbit was reduced to a cowardly wreck, which he’s not. Bonham Carter is fine as the Red Queen, and comparisons to Miranda Richardson’s “Queenie” in Blackadder are, I think, unfair if inevitable. (Bonham Carter’s Red Queen does owe a great debt to the historical Elizabeth I, though, I would say, especially as far as ERI’s penchant for favourites is concerned. And didn’t Miranda Richardson once play the Red Queen? Oh yes, here it is—Queen of Hearts. Hhmmm… now I’m confused. Is Bonham Carter’s character the Queen of Hearts from Wonderland or the Red Queen from Through the Looking Glass or an amalgamation of the two? Curiouser and curiouser!)

Mia Wasikowska is a wonderful young actress, as anyone who saw her in In Treatment will know, and she’s perfectly fine in this role. She’s not the Alice we all know, of course—her Alice is a rather worldly young woman, not Carroll’s “dream-child”—but a completely original character who better suits the modern, feminist sensibility I mentioned earlier. Whether or not any of that works for you?—well, tell me in the comments.

The film has Burton’s characteristic “look”, and at times I did find it a bit on the dark side (actually, not metaphorically, although that too—the heads in the moat bringing to creepily literal life the Queen’s trademark cry “Orf with their heads!”) and I also found it quite hard to hear what people were saying at times. (Most of those afore-mentioned new character names were lost on me. And again, I think they were unnecessary.) It was Wonderland meets Corpse Bride via Coraline as far as the set design goes, which I guess is to be expected (although I note that Burton was not involved in Coraline, but its director, Henry Selick, worked on The Nightmare Before Christmas with Burton).

But frankly, I’d rather have seen Burton’s take on the original Alice story. He clearly knows it intimately, or his screenwriter does (the detail of the film proves this), and has an empathy with for its darker, surreal moods, so why not just let him have his not inconsiderable head with Carroll’s world and see what he came up with? Alice doesn’t need modernising—she’s a girl for the ages, as so many pre-adolescent heroines of children’s literature are, from Alice through Anne Shirley and Judy Woolcot to Lucy Pevensie and Calpurnia Tate—before puberty and the imperatives of potential womanhood begin to hit home.

So no, I didn’t hate it. I liked a lot about it. I’ll see it again (I didn’t see it in 3D and actually, I feel absolutely no desire to) and probably buy the DVD. It’s not terrible, but we’re still waiting for an imagination to match Carroll’s to really bring Alice to the big screen.