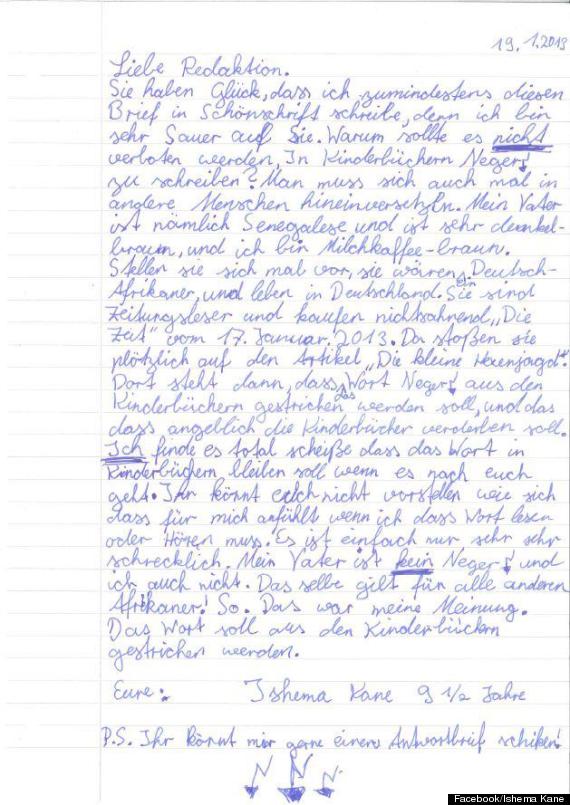

There’s a story on the Huffington Post today about a young girl, Ishema Kane, in Germany who wrote to the newspaper, outraged at their defence of racist language in children’s books—specifically, Pippi Longstocking. As letters of outrage go, it’s pretty fabulous. I especially love this bit: “I find it totally shit that this word would remain in children’s books if it were up to you.” You go girl! (She’s only 9.)

(I also note that the N word under scrutiny is apparently ‘Negro’, not the other N word, and am interested that this word appears in this instance to have caused as much distress and impulse to censor as the other, more commonly offensive N word. However, that’s a slightly tangential point to what I want to address here, but if anyone has any thoughts on that, please share.)

Now, this is not the first time this topic has raised its head in children’s literature circles, not by a long shot, but I posted the story on Facebook and it engendered very interesting discussion that I thought I’d bring over here to the blog.

But before that, let’s have a bit of an overview, at least from my point of view, of how I’ve experienced this debate. I think it first raised its head for me back in the 90s when the Billabong books were reissued with the more, by contemporary standards, offensive language and attitudes towards Australian Aboriginal people removed. Sanitised. Censored. Depending on your point of view. (And look! I wrote about this back in 2006!)

The child_lit community has debated this topic many, many times over the years, particularly as it relates to portrayals of Native Americans (the list being US-based and mostly made up of US children’s lit professionals and enthusiasts). The discussion has often been spear-headed by the women behind the Oyate site, which provides reviews and resources on books by and about Native Americans—and doesn’t pull any punches when it finds books and authors it finds objectionable. (See also Debbie Reese’s blog American Indians in Children’s Literature.)

These discussions on child_lit sometimes became very heated, especially when heart-held favourites, and strongholds of the canon—such as The Little House on the Prairie—were cited as books that could, had and continued to cause great hurt to Native American children who come across, or worse, are forced to read the book in school (because if you come across it yourself, you can chuck it across the room. If you have to read it for school, not only do you have to read it, but its very place on the reading list gives its attitudes and language an imprimatur).

I don’t know that Debbie Reese and her colleagues were arguing that bonfires of the Little House and Little Tree books should be lit across the land, much as maybe they privately wished that to be the case, but they were (are) determined to continue talking about this issues, difficult as it is for all of those of us who held Laura and Pa and the Billabong gang so close to our hearts as we grew up, then and now.*

My idealised view has long been that if the books hold values that are so anathema to contemporary values, then the books should be allowed to quietly disappear into the archives. I’m not a fan of tampering with a writers’ work/words/intentions, especially when they are not around to contribute to the discussion/editing process, no matter what the Estate might have to say about it.

But of course, it’s not as simply as that. Books don’t just quietly go away. First of all, what’s to stop people, even children, coming across them in secondhand bookshops, or in libraries with a conservative culling policy, or on the shelves at Grandma’s house. Perhaps more potently, though, there’s the nostalgia value: parents, aunts and uncles, grandparents and teachers who want to share beloved books from our own childhood with the kids in our lives and classrooms. Sometimes we’re shocked to find what lurks in those beloved pages, and maybe we think twice about passing them on, or maybe we excuse those transgressions away with the argument that those attitudes are from another time when people didn’t know better. (Except that they did.)

There’s also the cultural argument: many of these books have stood the test of time, and still are popular and have much to offer readers now. Do we throw the baby out with the bathwater—you can read 6 of the Narnia books, but not The Horse and His Boy. (Or, arguably, The Last Battle, especially if you want to add sexism into the mix, but I think it’s fair to say that people get more upset about racist attitudes in children’s books than archaic sexist attitudes. I’m not sure why that is and don’t have time to think about it right now, but I’m keen to come back to it at some point.)

So if we operate on the assumption that most of us are pretty much bottom-line against censorship, as in outright banning these books, and we accept that these books aren’t likely to just magically disappear on their own account, what are we left with?

We reissue them with changes to language and attitudes—mid-range censorship. Or we let them stand as they are, reader beware. Treat them as a learning opportunity. Do Not Whitewash the Past. But at what cost?

As I said, I posted the German story on Facebook, and the first response I got was from my friend Gayle Kennedy, a wonderful writer for adults and children, who is a a member of the Wongaiibon Clan of the Ngiyaampaa speaking Nation of South West NSW. Gayle’s not backward in coming forward in expressing her opinions on, well, anything, so when she just posted a quizzical ‘Hhmmmmm…’ in response to the post, I was curious to find out what she REALLY thought.

I don’t like people fucking with other people’s writing. Simple as that for me. I can’t bare what’s being done to the texts of yesteryear. How are you going to learn from the past (mistakes and all) if you keep sanitising it? Sanitising these book means that kids these days do not have the benefit of seeing how far society has come in terms of how we see other people and society in general. Why not point out to the kids that these words and terms were used all the time in that day and age and how society has grown and realises now the harm and hurt it caused and still causes. There are lessons to be learnt from confronting these texts head on and none of from running away from or excising them.

*I’ve personally never actually read a Billabong book, and while I read the Little House books as a child, it was the TV show that won my heart. As the name of this blog attests, my best-beloved childhood book of this kind was Seven Little Australian Australians, which actually had a passage sympathetic to Aboriginal people removed after the first edition, not to be restored for 100 years.