The Gathering by Isobelle Carmody

This review was first published in Viewpoint: On Books for Young Adults Volume 1 Number 3 (Spring 1993)

“Do you believe in good and evil, Mum?” I asked… “…I mean evil as a sort of force that you could fight.”

She frowned. “Evil and good are potentials in all of us. You have a choice whether or not to be evil because you can choose not to do evil things…. Sometimes it might be tempting to do a bad thing and if you resist then that’s fighting evil. But a force outside human beings?” She shook her head.

…It was just the sort of explanation an adult would have. My mother could only see evil in a mundane way, like stealing or lying or cheating on your income tax …kids could see things that adults couldn’t because they weren’t hampered by ideas of the way things ought to be.

In discussing fantasy and her indebtedness to the hero-quest, Diana Wynne Jones made the observation that “the reason the heroic ideal had, as it were, retreated to children’s books, is that children do, by nature, status and instinct, live more in the heroic mode than the rest of humanity… in every playground there are actual giants to be overcome and the moral issues are usually clearer than they are, say, in politics.”* It is in this same spirit of belief in the child — or young adult — as hero that Isobelle Carmody has written The Gathering.

The Gathering is, at its simplest level, fairly familiar territory; a community is threatened by an infectious evil, represented by conformity and control, which only a small band of young people — The Chain, as they come to call themselves — can recognise and overcome. It is the story of Cheshunt, a seaside district that is a apparently a “good, safe neighbourhood”, but is in fact infected by evil. The apparent order in Cheshunt is maintained by gangs of youths who only barely — and only sometimes — manage to keep their malice in check. The novel’s narrator Nathaniel has just moved to Cheshunt, and he loathes it — the cold wind that penetrates glass, and the oppressive stench from the abattoir that overlooks his school. Nathaniel is victimised by the school patrol and Three North High’s deputy Mr Karle when he refuses Karle’s “invitation” to join the youth group known as The Gathering, and his trouble at school further damages his already shaky relationship with his mother. While out walking with his beloved dog The Tod he finds himself drawn several nights running to the school grounds, where he risks both breaking the curfew in place in Cheshunt, and attack by the packs of feral dogs that roam the town. It is at the school at night that Nathaniel meets the five other students who have been drawn together to recognise and defeat the evil that threatens to consume the town.

It is common in conventional versions of the hero-quest to find that the narrative is propelled along by the plot — action, and lots of it. And up to this point in The Gathering we are on familiar ground, with devices and plot elements that we frequently find in the fantasy-quest where the battle against evil is most commonly fought; Carmody herself has explored comparable ideas in her earlier Obernewtyn novels. But despite its obvious debt to the conventions of fantasy and the heroic ideal, The Gathering does not rely for its impact on an exciting plot and an atmosphere of mystery and suspense, although she has given her readers both these things. Instead, a great deal of The Gathering‘s ability to hold the reader until long after bedtime is a result of the consistent and wholly authentic narrative voice of its central character, Nathaniel Delaney.

Nathaniel’s first person narrative acts as far more than merely a device to help the reader “relate” to the central character; the immediacy of his voice is essentially linked to Carmody’s exploration of the nature of evil. Evil in The Gathering is an independent force that infects ordinary people; or rather, that ordinary people allow themselves to be infected by. Carmody shows it to result in the kinds of ills that are genuinely of concern to young people; domestic violence, child abuse, police brutality, the failure of parents, guilt. The force of evil that exists in Cheshunt is not explained as it may have been in a purer fantasy tale as some supernatural force deliberately and malevolently interfering with human society (and it should be pointed out that although Carmody draws on devices from it, The Gathering is not fantasy). This evil simply is, and it is manifested when it finds those willing to act on its behalf. In The Gathering, this usually happens when those with a perceived authority; police, teachers, parents, allow their power to dominate and become corrupted. Nathaniel’s struggle to understand both the nature of this evil and its place in his own history is actually more significant to The Gathering than the specific details of “goodies and baddies”, or the mechanics of the evil.

This is certainly not to imply that the plot of The Gathering is insignificant or uninvolving. To the contrary, elements of the plot such as Nathaniel’s investigation of the murder of the school’s caretaker some decades earlier, and the mystery surrounding his own family are not only intriguing in themselves, but reflect back onto the novel’s concerns with the nature of evil and the impact of the past on the present. It is also a book that throws up fascinating details on each new reading, such as the reference to a student of Three North from many years back named by Emily Bronte’s pen-name, Ellis Bell. This detail could not help but make this reader consider the inspiration for Carmody’s masterful evocation of place and landscape as symbol, which is largely evoked in a most unusual way through a remarkable depiction of the sense of smell. Other literary references are scattered throughout; the members of the Chain refer to Karle as “The Kraken”; Nathaniel reveals that he was named for Nathaniel Hawthorne. The school library is named as a sacred place safe from the evil; all of this raises intriguing possibilities about the place of literature and the written word in the fight against the dark forces in our – or any- society. Indeed, in nearly every aspect of this novel, Carmody is rather more interested in raising questions than answering them, and thus it is a novel that the reader can return to to further explore her ideas and philosophies.

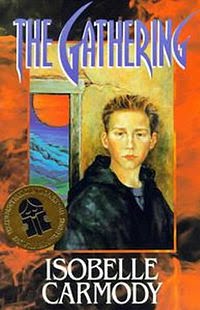

The Gathering has provided for this reader at least, an enormously challenging and satisfying read; one frequently gets the feeling that the novel was also deeply challenging to write. Carmody has drawn together some quite disparate elements from fantasy and social realism to create something quite complex and stunning. It also happens to have one of the best covers of any novel of any year. The novel’s editor, Erica Irving, describes the book as Carmody’s breakthrough novel, and both the tale and its telling will confirm this book as a major achievement for Carmody, and create an important place for The Gathering in contemporary fiction for young adults.

*Diana Wynne Jones, ‘The heroic ideal – a personal Odyssey’, The Lion and the Unicorn, v.13:no.1 (June 1989)