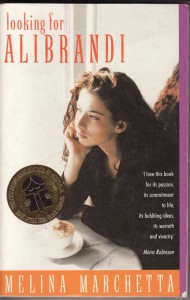

This interview was one of the first with Marchetta after the publication of her first novel. Looking for Alibrandi quickly became something of a phenomena. The book became a cross-over success, and was listed as a senior high school English text. Some years later, the book was made into a popular feature film, with an award-winning script by Marchetta herself.

Melina’s inscription on my battered first edition copy of Alibrandi says “thank you for writing what I consider my best interview”. I’m unashamedly proud of that, especially as I had put the microphone into the wrong jack and so had to write the interview from memory (I checked the interview with Melina prior to going into print, I hasten to add).

I’m also enormously proud that this interview, one of the first articles I had accepted into print, was also the cover article for a then brand new journal, Viewpoint: On Books for Young Adults — Volume 1, Number 1 — 1992. Was it really that long ago?

Since it publication in October of last year (1992), Melina Marchetta‘s debut Looking for Alibrandi has provoked widespread praise and affection remarkable for a young adult novel; the all-to-familiar story for authors and publishers of children’s books is the long term struggle for recognition from the mainstream “literati”. Reviews for Alibrandi, however, have been almost without exception excellent; the reaction of author and Sydney Morning Herald columnist Margaret McClusky, for instance, who said “A must for all teenagers… Buy it for your H.S.C .- swamped offspring before it is too late.” (SMH. 14.11.92) being quite typical. The attention has been both exciting and overwhelming for Marchetta, who has nevertheless kept a clear vision of both her current success, and her on-going career as a writer.

A notable feature of Marchetta’s writing is the controlled, understated tone of her protagonist Josephine’s narrative. Integral to this tone is humour, frequently self-deprecating and even defensive on Josephine’s part, and always sharp, observant and revealing. It is interesting to discover, considering its intrinsic value to both the narrative and the character of Josephine, that Marchetta did not consider the book to be particularly funny, until readers began laughing aloud at passages such as this;

Religion class, first period Monday morning, is the place to try to pull the wool over the eyes of Sister Gregory. (She kept her male saint’s name although the custom went out years ago. She probably thinks it will get her into heaven. I don’t think she realises that feminism has hit religion and that the female saints in heaven are probably also in revolt.

Indeed, the opening of the novel is predicated on a joke, with Josephine managing to talk her way out of trouble in the first lesson of her last year at school. It serves as an excellent introduction to the character of Josephine, who is intelligent and dramatic, funny and observant as well as being quite self-absorbed. Similarly, this opening passage lets the reader into some other of Marchetta’s interests in telling the tale of Josephine’s coming of age; religion, sexuality, feminism, and the importance of female friendship and guidance to this maturing young woman. Well into the chapter, after the reader has begun to develop an understanding of who Josephine is, she begins to address her experiences as an Italian-Australian;

…primary school was the only time I was people I could compare notes with and find a comfortable place alongside. We’d slip our Italian and Greek into our English and swap salami and prosciutto sandwiches at lunch-time and life was good in the school-yard. Life outside school, though, was a different story.

Much of the discussion of Alibrandi has centered around this portrayal of a multi-cultural Australia, although remarkably, the novel has managed to largely avoid the negative and superficial “issues” pigeon-holing so much realist fiction for young adults is victim to. There is no question that Marchetta’s own experiences as an Italian-Australian have informed her story. Nor is there any doubt that in Josephine Alibrandi she has created a fresh non-Anglo-Australian voice of great power and integrity. Nevertheless, Marchetta does find that the focus on the Italian heritage of her protagonist (and herself) can be both distracting and limiting; it was not, she says, her first impulse in telling Josephine Alibrandi’s story;

I was fascinated by my Nonna’s experience of leaving her family when she emigrated to Australia 60 years ago. I am very close to my own sisters, and I couldn’t imagine having to leave them forever. So I wanted to explore that experience; what must it have been like for women like my Nonna to never see their families again? Out of that came the relationships between the women from three different generations. I think that is the most important part of the book, and it’s those relationships that I wanted to write about. I certainly never intended to sit down and write a book about racism, or about suicide or about any of the other “issues” that might have ended up in it, and I really hate the thought that it would be used as bibliotherapy; “here’s this book that will solve all your problems with racism” or whatever.

Another legacy of the shared Italian-Australian heritage of both author and protagonist is the common assumption that the book must be autobiographical. I suggested to Melina that this reading of her novel is in some ways complimentary, being as it is an indication of the kind of response readers have to Josephine, and to the lively and truthful tone of the novel; Marchetta has captured her characters, their situation and the inner city suburbs of Sydney acutely and precisely.

One letter I got was from a girl who’d read the book, and she was driving through Glebe, and she said she kept expecting to see Josephine walking along the street. It was great to think that someone had felt this way about Josephine, that she could be real, but it’s definitely not my autobiography. Of course my experiences as an Italian-Australian are there, and I’ve used things like my Nonna emigrating, but people ask me things like “Who’s John? Is he really a politician’s son?” I didn’t base the characters on anyone, although I can see parts of myself in Josephine, and friends have recognised things about themself that I didn’t consciously put in. But I would really hate it if people thought it was my family depicted, and in some cases it would be very hurtful to my family if people thought so. It would be terrible if people thought, for instance, that Christina’s father was my mother’s father. My mother adores her father, and while he was a stern man, like Christina’s father, he adored his children and his wife. And the relationship between Marcus and Josephine’s Nonna is completely fictitious, although I did have grandparents who lived in the far north of Queensland.

A key interest of the novel, of course, is Josephine’s development towards a mature understanding of herself, and thus the ability to make informed choices about her life and relationships. Indeed, Marchetta’s working (and preferred) title was The Emancipation of Alibrandi. A pivotal experience in Josephine’s story is the suicide of her close friend John Barton; his death provides her with a tragic perspective for her own life and problems;

… The day John died was a nose-dive day and I hit the ground so hard that I feel as if every part of me hurts. I remembered when we spoke about our emancipation. The horror is that he had to die to achieve his. The beauty is that I’m living to achieve mine.

I asked Melina if she had consciously worked towards John’s death both as an emotional meeting-point for much of the novel’s concerns, and as a catalyst for Josephine’s emancipation;

Not at all. I actually spent a lot of time resisting killing John at all. I knew from the start that he would have to commit suicide, but I really didn’t want to do it. If I’d had more time with him, he could have worked things through, but given that the story was just one year in Josephine’s life, it wouldn’t have been honest to rush him on to a happy ending; it would have been ridiculous if he suddenly turned up at the end of the book saying, “hey, I’ve told Dad I don’t want to be a solicitor and everything’s OK.” His death was the only way I could finish his story given those constraints, and I guess it just became a natural point for things to come together, in terms of the structure and so on.

Marchetta did not have a particular audience in mind when she set out to explore these relationships, and in developing her central themes and characters. She credits her editor at Penguin, Erica Irving, with giving her the time (Penguin worked on the manuscript with Melina for three years before publication) and encouragement to focus what was an unruly manuscript on an audience, and to develop a cohesive and controlled story-line. This inevitably led to some significant changes from the book’s early drafts;

Christina and Michael were much more important in the early drafts. I was really interested in their relationship, and I particularly like Christina; I would have liked to have dome more with her. But the book was much too long, and I needed to concentrate more on Josephine, so I had to push them into the background a bit, which I’m sorry about. I also had another girl in Josephine’s group of friends, in fact, she was Josephine’s best friend, so I was a bit surprised when I realised she was the one that had to go. But again, it really was too long and messy, and by cutting out this best friend, who it turned out Josephine didn’t need anyway in terms of the plot, I could bring Lee into it much more. She’d been in the background a bit, but I always really liked her, and I still think she’s one of the most interesting characters in the book, so that worked out well.

Nevertheless, it is Josephine Alibrandi who is the novel’s driving force, and who is, perhaps, largely responsible for the warm reception the book has received. It is fascinating, then, to discover that Marchetta herself finds a lot about Josephine that she dislikes, and is surprised that readers have been so overwhelmingly positive in their responses to her;

She’s a bitch! She’s so selfish, and she can’t begin to see that other people’s problems are worse than her own. I kept telling a friend of mine this, and she couldn’t see what I was getting at until she’d read the book three or four times, and then she said to me, “I see what you mean about Josephine!”

The ambivalence Marchetta feels towards Josephine is revealed through the characters of Sister Louise, her headmistress, and her boyfriend Jacob, neither of whom hesitate to point out to Josephine when she is being selfish, over-dramatic, or plain stupid. A quite shocking example of this is in the scene where Jacob rescues Josephine from a violent mob of teenage boys in a McDonalds carpark, and then abuses her for her stupidity in spitting on and further antagonising the ring-leader. It is an indication of the exasperation that Josephine provokes in those who care about her, and Marchetta agrees with Jacob that Josephine’s dramatic and impulsive behaviour too frequently land her in avoidable unpleasantness. To be fair, Josephine can be fairly hard on herself, and her ability at and willingness for self-scrutiny develops as she matures. It is testament to Marchetta’s care in balancing the complexities of Josephine’s character that the reader can witness her tantrums and drama-queen turns, her often thoughtless and selfish actions, and yet know that this is an essential part of her emancipation, and that it does not detract from her vitality, compassion and intelligence.

That Marchetta has achieved such a smooth and involving synthesis of character, contemporary experience, humour, complex relationships and genuine emotion in what is not merely her first novel, but her first published work of any kind, is indication of a remarkable talent that will be fascinating to watch develop.

Marchetta is working on a second novel, but stresses that she is not going to rush the writing of it in order to quickly follow up Alibrandi‘s success; “I’m a careful person, and I am quite happy to spend a couple of years on this novel to make sure I get it right. ” Undoubtedly, expectations will be high, and Marchetta is determined not to be limited by this, or by the perception that she is a particular type of novelist:

The novel I’m working on at the moment is really different to Alibrandi. It’s a mystery, and it’s set in a country boarding school, I’ve had to do a lot more research, and it won’t be “multi-cultural” at all.*

I asked Melina about her approach to writing, and how she is currently fitting in the writing of her second novel with her university studies. Does she write regularly, and does she write to a plan? She began her answer with a wry smile.

I heard Gary Crew speak at the (Sydney) Children’s Book Fair a couple of years ago, and he showed us his writing journal; it was fantastic, all laid out with diagrams and so on. I rushed straight out and bought one, but I never used it! No, I don’t have a plan, I just write to begin with, and then I find that about ten chapters in I have finally got my characters; then I have to go back and re-write the early chapters, because I find that the characters are really flat and undeveloped in them. This is about where I’m up to in the second novel. And I do find it really hard to write while I’m studying; I keep telling myself, “next holidays!”

*Eagle-eyed readers will have spotted that Melina is here referring to her Printz-award-winning novel On the Jellicoe Road (Jellicoe Road in the US), which was not published until more than ten years after this interview. Writing is work, people.

I really love this book! Its definatlye my fav i rate it 9/11