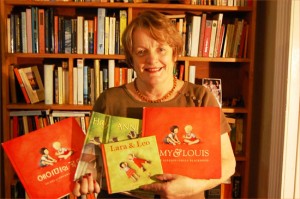

This interview was first published in Australian Women’s Book Review in December 1994. Libby Gleeson is not just the author of numerous picture books and novels for middle year and young adult readers, she has been a true force in promoting the status of Australian children’s authors and illustrators in the wider literary community. Libby has been Chair of the Australian Society of Authors and she was instrumental in securing Educational Lending Rights for Australian authors and illustrators. Her picture book The Great Bear, illustrated by Armin Greder, was the first Australian picture book to win the Bologna Ragazzi award. Libby is a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) and recipient of the Lady Cutler Award for Services to Children’s Literature in NSW.

Libby and I have been friends for many years, and over the past four years, we’ve also been colleagues. Libby is the Chair of the Advisory Group to WestWords: the Western Sydney Young People’s Literature Development Project—my day job. Libby is directly responsible for securing the finding for WestWords, and is a great personal and professional support to me, and champion to the project. She continues also to be one of our most consistently interesting writers for young people.

_________________________

Since the publication of her first novel Eleanor,Elizabeth in 1984, Libby Gleeson has enjoyed both popular success and critical appreciation. She is frequently asked to speak on matters involving writing for children, and has gone on the record several times with her views on issues such as censorship, and girls and fiction. With fellow writer Nadia Wheatley, Libby holds the Children’s Writing portfolio for the Australian Society of Authors. Her latest novel Love Me, Love Me Not was shortlisted in this year’s (1994) Children’s Book Council Awards. Libby recently discussed her work and her thoughts on some of the politics involved in writing for children with Judith Ridge

There was a movement through the 70s and 80s to address the problems in representation of girls in fiction. The current discussion about gender and fiction seems to be about boys; boys don’t read, how do we get boys reading? They are different issues, because boys have always been well represented, but has the work been done for girls in fiction?

It’s an interesting question Certainly I think I would have been part of that movement. My first two novels were definitely conceived in that climate. In my own work, I feel as though to an extent it’s been done; I cannot keep writing the same books over and over again, but I don’t think it’s true that it’s been done in the wider context. I had an interesting conversation with Tessa Duder at the Melbourne Festival last year; somebody in New Zealand is doing a Ph.D thesis where they’re doing a simple count of representation of girls in fiction. I think she said it’s hitting 30%, which suggests it’s just another version of the old glass ceiling. I also think there are still plenty of books being written where the rôles are no different than they were many years ago. And you’re right, it’s a very different question to the “boys reading” one. That’s all about access, about the way boys are taught, about the way reading is perceived. I don’t think that it’s a question of roles and of images of boys presented in fiction.

Books for young people are frequently categorised and assessed according to social issues or political viewpoints. You’ve said that you’d be very resentful if, for instance, I Am Susannah was categorised as a “single parent” novel, and rightly so. So where do your personas as writer and as a political individual intersect, and how do they remain apart?

Can I have it both ways? I sort of feel I can. What I would find insulting would be the perception that a book is about only one thing, and certainly, although I am quite willing to stand up and say that Eleanor, Elizabeth and I Am Susannah are books about feisty young girls, they’re also about a lot more than that. I think that it is insulting to categorise quality fiction in terms of one issue when it’s quite obvious that they are complex and many-layered works in the same way that fiction for adult readers can be. It’s all part of the same push, I suppose, to moralise about children’s literature, and to assume that it only has an educative rôle. It comes down to whether you are writing books that are ideology-driven or story-driven, and in my case I would hope always that they are story-driven.

Personal and family history, and the child’s need to learn something of these things is quite important in much of your work. Is this a conscious element of your writing?

Yes, I think it is. It’s all part of a personal philosophy, that a person is the product of the environment to which they’re born, the people they grow up with, the personal heritage is that shared history that’s passed on. Of course, it is passed on far more through the female line than it is through the male, and that’s largely because of the intimacy of female conversation. I’m a great gossip, I think gossip is the most justifiable activity, and it’s like a lot of women’s behaviour that’s denigrated. One of the qualities that makes a person a fiction writer is their personal interest in human beings and their behaviour and their relationships and the small movements in the pathway of their lives which cause change and development. And so one of the things I’m really looking at is the way in which your past influences your present, which of course will conspire to create your future.

The protagonists in Love Me, Love Me Not are further along in their emotional and sexual path than in your earlier books. Have you finished with the themes relevant to the younger children; the identity theme, leaving childhood and so on?

I don’t think so. As soon as I say that, I’m going to get an idea for another book about 11 year olds! I don’t think it’s as neat as that. And I’m certainly not finished with the 14 year olds. Life’s not linear for me. I’ll be oscillating for a few years yet.

Two stories from Love Me, Love Me Not were previously published; had you written them as isolated stories that ended up in Love Me…, or were they always intended to be part of the longer work?

They didn’t start out to be part of it. The first story I wrote was called “In the Swim”, for Landmarks. I had just finished Dodger, and I was in that stage of “I can’t start another big novel yet”, and it intrigued me that I might start writing a collection of stories, but the idea didn’t really gel until I was invited to make a contribution to Goodbye and Hello. I wrote “Her Room”, which subsequently became “Fran”. Once I had those two, I really started to think, “hang on, there’s a connection between these”. The other factor that had come in was that a couple of teacher-librarians had said to me, “why don’t you ever write about love?” And I’d said, “I write about love all the time, what do you think those other books are about if it’s not love?” But of course, they were talking about early romantic and sexual awareness and so on. I was intrigued with the idea of writing about the early stages of those relationships. “Maria” was the one that came next. They’re certainly not written in any order, that’s the other thing. And so I had the three of them, “Fran”, “Cass” and “Maria”, and I really started to think, “well, hang on, if this is going to be a collection, how’s it got to work?” And I decided then, it’s got to have male protagonists as well as female, and there has to be some happiness in all of this, because there are some kids who at 12 or 13 are very competent, and do have happy relationships with the opposite sex. And so I went back into the Cass story and looked at all the other characters that were there, and pulled out individuals, and then re-wrote the Fran story with those characters moving into that as well. And so I wrote the series.

The last story, “Cathy and Rodney” is interesting on lots of levels. It’s the only story that you use first person in. Secondly, Cathy and Rodney have been a bit of a figure of fun, from the other kids’ points of view. They’ve been objects of jealousy, of derision, of all sorts of things. And so they’ve been wafting through as figures, rather than characters, and then you bring them up front in the last story. Now, I gather from what you said, you weren’t necessarily deliberately aiming to that end…

No, although it was obvious that they were sufficiently significant in the other stories that they had to have a story themselves. And I did really want to show this relationship where people were having a go at working out things. I really felt I had to write a story for one or other of them, and it became increasingly obvious that this was an opportunity to write a joint one. It was obvious that it should be the final story, because they were the only ones who were making a go of it. I thought at one stage that maybe I shouldn’t write in the double voice, that it would be too great a divergence from the way the other stories were written, but I really wanted to single these two out as different.

Did you work very hard at achieving the third person voice that’s used throughout? You’ve balanced it very well; there is a level in the narrative voice that’s detached and observational, but at the same time very sympathetic and understanding to the characters.

Yes, that is obviously very, very carefully constructed, and I hope it works all the time. The hardest to write were probably the two boys, Pete and Troy, but I was determined to write from their point of view as well, and I can only hope it came off. The choice of story was consistent with the tone of the narrative voice, I hope.

Your books often end on a very “up” moment. Is this the mood you want to leave the readers with?

Yeah, I think it is. It also seems the appropriate moment. The endings are optimistic and they’re hopeful, but I don’t think they’re illusory, and they’re certainly not neatly tied off. One of the things I’m really trying to say is that this is a slice of life, but it goes on, and who knows where it goes after this? I want the reader to see that there’s this potential for hope and other possibilities.