Source: About ‹ Misrule — WordPress

Category Archives: Misrule

Dr Maurice Saxby AM: In Memoriam

Maurice Saxby, 26 December 1924—2 December 2014

I met Maurice Saxby the first time I attended a meeting of the NSW Branch of the Children’s Book Council. I was in my mid-20s, and I had not long since decided that I wanted to make children’s books my life’s work. I had met Ros Bastian, who was at the time the coordinator of the annual Children’s Book Fair, during my postgrad studies in Children’s Literature at Macquarie University, and she encouraged me to join the CBCA. And so I came along to the AGM, circa 1990, joined the committee and began my work in children’s literature.

And of course Maurie was there. He was the CBC’s first President in 1958, and remained an active member his whole life. I didn’t know anyone or anything much back then—I didn’t know who Maurie was, but I quickly learned. He was of course, as we all so affectionately called him, the Godfather of Australian Children’s Literature. In addition to his work with the CBC, he established studies in children’s literature at university level, and thousands upon thousands of primary education and teacher-librarian students trained under his guidance. There is no doubting his influence in establishing Australian children’s literature as a core part of the curriculum in Australian schools, and in promoting its value and quality to the international children’s literature community.

And of course, he was its great chronicler. Soon after that first CBC AGM I found copies of Maurie’s History of Australian Children’s Literature in the library of the school where I worked at the time—from memory, they were being discarded (!) and I snaffled them. Of course, Maurice went on to revise that history, and its three volumes—Offered to Children: A History of Australian Children’s Literature 1841-1941, Images of Australia: a History of Australian Children’s Literature 1941-1970, and The Proof of the Puddin’: Australian Children’s Literature 1970–1990—published and expanded in the 1990s, remain core texts in my professional library. I refer to them all the time. They are my Bible, my most comprehensive and reliable (if also opinionated!) source, and will be in the pile of treasures to be saved come flood or zombie apocalypse. I believe Maurie was working on Volume 4—I hope it was finished before we lost him, this week, just shy of his much-anticipated 90th birthday.

Going back to that kid’s lit newbie back a quarter of a century ago—Maurie welcomed me into the fold as if I’d always been there. His generosity of spirit and his passionate commitment to his field rendered him, where it really mattered, ego-free. (He wasn’t ego-free about everything, including his own writing, but that’s not remotely a bad thing.) He wanted advocates, he wanted people to be as in love with children’s books as he was, and anyone who wanted to roll up (and roll their sleeves up) and be part of the community was in, as far as he was concerned. That’s certainly how he made me feel. He always treated me with the greatest professional courtesy, and the warmest personal affection. (Maurie was a kissy man. I think we’ve all received a smacking greeting from him.)

Maurie also had a slightly acerbic side; he knew too much and was too smart to suffer fools privately, but publicly I never knew him to be anything else but charming, warm, generous and completely enthusiastic. And he was a great friend to so many—widowed twice and with no children of his own, his friendships sustained him over many decades. I don’t claim that degree of friendship myself. I am just honoured to have known him, and to have been the inheritor of his great work and legacy in bringing children and books together—and for welcoming me so whole-heartedly into the world that has in turn sustained me and brought me enormous professional satisfaction and some of the most important friendships of my life.

My dear friends Simon French and Donna Rawlins with Maurice Saxby at the Maurice Saxby Lecture, May, 2012

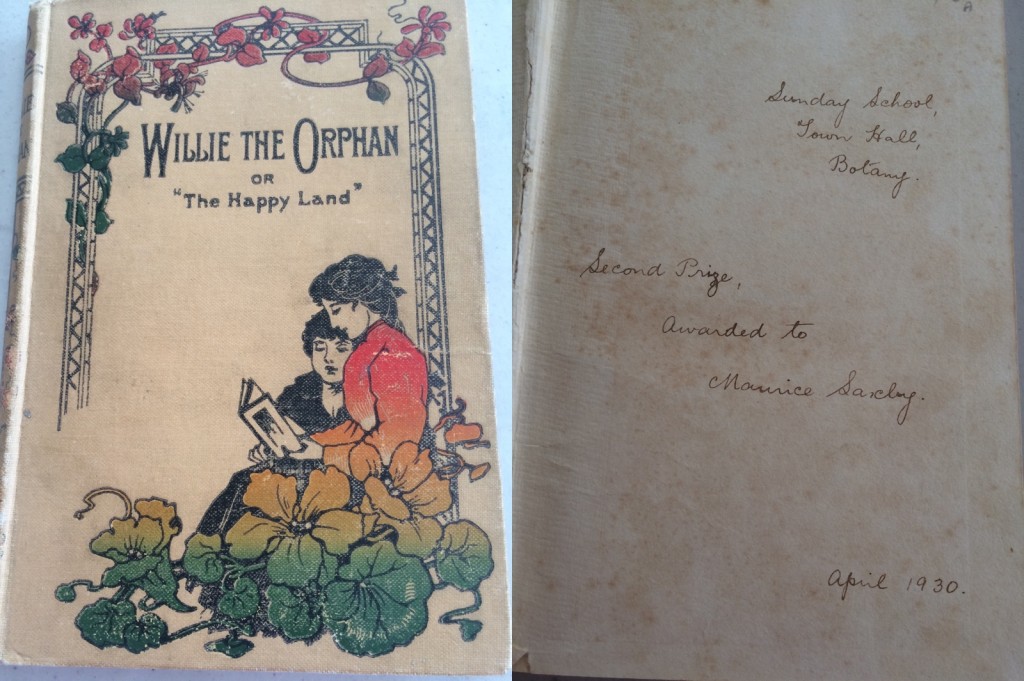

I guess it was a bit more than 10 years ago, I was browsing in a second-hand bookshop, and I came across a small stash of children’s books from the early-to-mid 20th century. Flipping through them, I was astonished and thrilled to see the neatly inscribed name of Maurice Saxby on the fly page of a book called Willie the Orphan, or, The Happy Land. At first, I thought, I must return this to Maurie! How did this end up here? But then I realised it must have been one of the books he sold when he moved from his home to a retirement apartment—and I was so pleased to have it. A book from Maurie’s library! How wonderful to have this on my own shelves.

Tonight, thinking about our beloved Maurie, I went to my shelves and took down the book, and rediscovered what I had forgotten about this treasured find—that it was a book given as a Sunday School prize to the five and a half year old Maurice Saxby.

Imagine that. Five year old Maurice.

It feels so fitting, to have a book that Maurie held and read and, maybe—I don’t know!—loved as such a young child. Perhaps one of the first books he could read alone. Because, thanks to Maurice Saxby, and all the people he influenced and befriended and converted, I was able to make a life in children’s books. In putting books into children’s hands.

I owe him so much.

And, as I said to Maurice’s great friend, Margaret Hamilton:

We will honour him with our work.

Read the damn books

A bit over ten years ago, I was writing a Master’s thesis on feminist retellings of fairy tales in novels for teenagers. My interest in fairy tale retellings was to analyse the books through the prism of both narrative theory—to investigate the robust shape of these stories over the centuries—and that of the strong feminist criticism of fairy tales that emerged during second wave feminism.

I’d never had cause to question the idea that fairy tales are bad for women, that they entrench sexist attitudes, reinforce the trope of the helpless woman, that they inscribe beauty as its own reward and marriage as a woman’s only marker of success. But to my surprise, my research led me to question the very foundation of that critical position.

There’s a seminal paper, Marcia R. Lieberman’s “Some Day My Prince Will Come: Female Acculturation through the Fairy Tale” (1972) that is, in a sense, the über-text of feminist criticism of fairy tales. But what I discovered during the course of my research, and numerous close readings of the paper itself, was that Lieberman mostly wasn’t talking about the tales themselves—the written versions of oral tales, or the original literary tales by writers such as Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, Charlotte-Rose de La Force, Charles Perrault or Hans Christian Andersen.

She was talking about the Disney animated feature film versions.

Lieberman’s argument, which was to become so influential on feminist literary theory and criticism, was not based on centuries of versions and re-versions of the stories—many of which were told or written by women from all cultural traditions—but on films that emerged from and reflected a particular 20th century, western, patriarchal and capitalist view of the world. It was a bit like reading the English essay where the student had skipped reading the book and had obviously only seen the movie. I have to assume, of course, that Lieberman was familiar with the written texts, but that’s not what her argument was based on, and the discovery seriously challenged my unexamined feminist prejudice against stories I otherwise secretly really loved.

And it reminded me again of a lesson I would have hoped all critics would have learned by now—don’t criticise something you haven’t read.*

I came late to this week’s brouhaha over Helen Razer’s anti-YA diatribe in Crikey’s Daily Review because when it hit the interwebs, I was actually spending the day with children’s author Stephen Measday and twelve 9-13 year olds at a writers’ camp we delivered this week at the day job. That’s what I do. I work with kids and teens who love to read, and who love to write. I’ve been doing it for nearly 30 years, one way or another, and in the course of that time, I have read thousands of children’s and young adult books, and I’ve written about them quite a lot, too. Books by writers from all around the world, everything from wordless picture books through the simplest series fiction for reluctant readers to challenging literary fiction for older children and teenagers. It’s a huge field, and a broad church, which includes books for young people of all ages, from pre-literate pre-schoolers through to sophisticated older teenagers. And it’s one that attracts some of the most rigorous literary study from academics all around the world.

But there’s one thing it has—or ought to have—in common with any other art form, literary, visual, performing, whatever. And that is, you don’t get to, with any credibility, write about it unless you’ve read it.

So I’m not going to critique Ms Razer’s article on that very basis—I haven’t read it. Because, seriously, why would I. (Plenty of other people have, though, and I will link to their responses at the end of this post.) Because I’ve read maybe dozens of similar uninformed and insulting arguments about children’s and youth literature, and the people who read it—including its primary audience, kids and teens. So I feel like I’m in a position to offer would-be commentators on the topic a few words of advice. So here they are:

Top Ten Tips for Writing about Books for Children and Teenagers.

1. Read the books. No, not just The Fault in our Stars or Hunger Games or whatever happens to be on the bestseller lists at the time. Read widely, read historically. The first books published specifically for children emerged in the 18th century, so you’ve got some catching up to do. Start now, and maybe in a few years time you’ll have the basis for some informed commentary on The Latest Big Thing.

2. Children’s and YA are not interchangeable terms. Children’s Literature and Young Adult Literature have well-examined and defining tropes, themes and forms. Yes, there are grey areas, but you won’t be able to write authoritatively about them until you know the parameters. Start with some of the excellent introductory academic texts on the subject: Perry Nodelman and Mavis Reimer’s The Pleasures of Children’s Literature or Michael Cart’s From Romance to Realism: 50 Years of Growth and Change in Young Adult Literature.

3. Do not patronise the readership. Young readers can be remarkably acute, astute and critical in their reading. And if you don’t actually like children and teenagers, then you won’t be sympathetic to their literature, so find something else to write about.

4. Don’t assume they read the same way adults do—they don’t. And don’t generalise about what all young people do or do not like.

5. Try and find some points of reference beyond Catcher in the Rye and Lord of the Flies. Same goes for writing as if JK Rowling invented the “witches at boarding school” genre. You are simply demonstrating the limits of your research and reading. In other words, see Point 1.

6. Be aware of the implicit sexism in your dismissive attitudes towards children’s and young adult literature. Despite the public profile of a handful of male writers, the field has long been dominated by women at every level; writers, publishers, teachers, librarians. This is not always reflected in awards or magazine feature profiles, but it’s the truth, and like all female-dominated professions, it attracts a lack of respect at best and out-and-out contempt at worst.

7. If you know your stuff, you may well be in a position to make some actually important and well-founded criticism of literature for young people, such as: the lack of cultural diversity in books for young readers, the heavy gendering of books, fat-shaming in kids’ and YA books, the lack of representation of characters with disability, and shamefully, in this country, the lack of LGBTQ characters and stories. Deduct points, however, if you ever entertain using the phrase ‘political correctness’ in your review/opinion piece/brain fart.

8. Remember that reading is a democratic pastime and stop being a fascist about what people can or should read. The truth of the matter is, there are more books now for readers of all ages, abilities and interests, and that is something to be celebrated, not condemned.

9. None of this is to say that children’s or YA books should be above thoughtful, critical analysis and discussion. On the contrary, those of us who have made children’s and YA literature our life’s work wish above all else that the books were treated with the same critical respect and rigour of any other form of literature. Honestly. Why else do we bang on about the lack of review space for them? We’re not masochists. We’d rather be reading.

Which brings me to:

10. Read the damn books. Thanks.

Look. I get it. We’ve all been guilty of bluffing at some point in our careers, but the truth is, you never get away with it, and when you’re taking someone’s good money to do so and trashing the status of a whole artistic and professional field you know nothing of and care less about? Shame on you.

Here are other people’s takes on Razer’s piece. They obviously have stronger constitutions than me.

Danielle Binks in Kill Your Darlings.

Ellie Marney at her blog hick chick click

Updated 3/10/2014 to add this direct link to Alison Croggon‘s excellent comment in response to Razer’s original article.

*Again, I am quite sure Leiberman read the damn stories. However, her interest was more socio-cultural than literary and the distinction between the numerous written texts and the Disney films was clearly of less interest to her than her overall thesis about fairy tales from a feminist perspective. If you want to know what conclusions I came to in my MA thesis, ask me, but I’ll have to go excavating for the file!

Kylie Fornasier’s Masquerade

Back on August 2, I spoke at the launch of Kylie Fornasier‘s debut young adult novel Ma squerade. I initially met Kylie through my work at WestWords, and since then, we have become friends and colleagues. Masquerade is Kylie’s first YA novel (she has published a chapter book and has a picture book scheduled for 2015), and there was huge buzz about it prior to the publication date. It’s getting rave reviews on Goodreads and blogs, and the clamour for a sequel is not going away. Kylie’s a top woman, and she has written a terrific book. Here is the speech I gave, with photos.

squerade. I initially met Kylie through my work at WestWords, and since then, we have become friends and colleagues. Masquerade is Kylie’s first YA novel (she has published a chapter book and has a picture book scheduled for 2015), and there was huge buzz about it prior to the publication date. It’s getting rave reviews on Goodreads and blogs, and the clamour for a sequel is not going away. Kylie’s a top woman, and she has written a terrific book. Here is the speech I gave, with photos.

*********************************

It’s both an hour and a pleasure to be here today to speak at the launch of Kylie’s wonderful YA novel, Masquerade. I first met Kylie a couple of years ago, in her role as teacher-librarian at Old Guildford Public School, when I accompanied the author-illustrator Leigh Hobbs to the school. Kylie had come in on her day off to host the visit, and if that wasn’t enough to convince me of her dedication to those kids and books, my good impression of her was confirmed by one of her students—a boy named Aaron, I think he was in Year 5 or 6—who had been working for some time on an epic spec fiction novel. Aaron stayed back after the session with Leigh was finished, keen to pick the visiting author’s brains as clean as possible, and it became evident that Kylie was a huge support to this young writer. She treated him seriously, as a fellow writer, and obviously spent a lot of time and patience with him, guiding him and sharing her own development as a writer as he worked on his novel.

Back then, Kylie was as yet unpublished, although her chapter book, The Ugg-Boot War, was contracted, and she spoke then of her YA novel-in-progress, and picture books she was working on. And it was quite obvious to me that this was no ‘wanna-be’, but that Kylie was serious not just about getting published, but serious about her craft. She was willing to do the work, and to give to her writing career the same attention and patience she gave to Aaron and I am sure, all her students, writers or not.

Since then, I have come to know Kylie as both a colleague and a friend. She’s shared with me her journey to publication, and I have offered her what support and advice I have been able to give. And she’s offered me some very welcome support in return, I can assure you. And when I say colleague, I mean that literally—As you know, I run the WestWords project for young readers and writers in greater western Sydney, and for the past year, Kylie has been the leader of our young writers group that meets every week at Blacktown Arts Centre. This dedicated group of young writers, aged about 12-15 years of age, get together every Thursday afternoon to develop their skills and share their writing. They even spent 12 hours of a day in their school holidays earlier this year writing a book for the Write a Book In a Day competition, run by the Katherine Susannah Pritchard Writers’ Centre, in support of children’s hospitals across Australia. And Kylie spent those 12 hours with them—and we weren’t paying her to do it, either. This one was their own initiative, led by Kylie, and another example of her enormous dedication to those young writers and to the craft of writing itself.

And I know Kylie is also an enormously valued, loved and respected member of a writers group that meets here in Penrith, and that she extends that support and dedication to her fellow writers, who this time happen to also be grown-ups. Some of those writers are acknowledged in Masquerade, and are of course, here today.

So that’s Kylie the teacher and mentor and friend—but what of Kylie the writer, and what of the book we are here to celebrate today? Well, the first thing I can say about it, is I loved it, and the scone thing I can tell you is that it is quite unlike any other YA fiction currently gracing the shelves of libraries and bookshops. I read a lot of young adult and children’s books, and I also read a lot of unpublished work—students work, from a course I teach, and manuscripts from various sources. And while often in there there is exciting and interesting work, there’s also a lot of derivative, middle of the road, and not very well-written stuff designed for what the author thinks is the current YA market. So, lots of moody teenage girls, generally very beautiful but not realising it until the object of their affection—who for some time now, has been either an angel, a demon or yes, a vampire—shows them their true beauty. Or at the other end of the spectrum, very dark, not very witty, explorations of the dirty end of realism. Or environmental catastrophes—those are usually not very funny either, as you might expect. And to a point, there’s nothing wring with those stories, except that we’ve seen so many of them, and the author’s point seems more to be about getting published than being a writer.

Kylie Fornasier, however, is a writer. I know this, not from what I know of her personally, but from having read her book. There is love and dedication to every aspect of storytelling on every page of this book. And there’s a joy and a genuine originality to her work that makes Masquerade such an absolute pleasure to read. In case you do not know the premise of the novel, it is set in 18th century Venice, the republic known as Serenissima, meaning “the most serene”. The season is Carnevale, and even without having read the book, if you know anything about Carnevale, you will know that there is very little that’s serene about it. Instead, it is a time of endless parties and secret assignations, of forbidden romance, of panoply and playfulness—mostly enjoyed by the wealthy merchant classes and aristocracy of course, but in Kylie’s Venice, at least, the servants also have their moments of mystery and adventure behind the masks and alongside the palazzi and canals of that most remarkable and romantic of all the European cities.

Kylie has organised her story a little like one of Shakespeare’s more complicated comedies—and it’s not accident, of course, that each section, or Act of the book, begins with a very appositely chosen epigraph, or quoit, from one of Shakespeare’s plays—mostly comedies, which of course in Shakespearean terms means romance—and mostly set in Italy. Or an Italy of Shakespeare’s imaginings, because as far as we know, he never went there, and of course we know Kylie has. More of that later. And like a great Shakespearean comedy, there is a marvellous cast of characters, laid out conveniently for the reader at the beginning of the novel like the cast of players at the start of a play—very handy to refer back to if, like me, you have trouble remembering names. And as in Shakespearean comedy, we have in Masquerade forbidden romance (and not a little sex!), mistaken and hidden identities, boys dressed as girls—and oh boy, do I want to know more about that Marco—, and girls dressed as boys. There are wittily bickering lovers, secret assignations, family mysteries, balcony scenes, sword fights, heroes of both sexes, villains and fools. (I fully expected one of the characters to be revealed to be wearing yellow cross-gartered stockings! That’s one for the Shakespeare nerds among us.)

I said earlier that there is love on every page of the novel, and it’s evident that Kylie really loves these characters, even, perhaps especially, the wicked ones. Each is precisely drawn by character and voice, and in some instances, by costume—there’s that theatre analogy again. Indeed, so lovingly described are the costumes that I am just waiting for the first, not fan fiction but fan illustration tumblr, where some dedicated young reader will bring to life each of the gowns, masks, cloaks, swords and other deliciously described props and costumes that adore both the characters and the book itself.

Unlike most YA fiction, there are as many storylines in Masquerade as there are characters, and bucking a trend that goes back decades, the novel is written in an assured 3rd person narrative voice. No clichéd first person YA voice here. There’s a confidence in Kylie’s narrative voice in Masquerade that belies the fact that this is only her first published novel. We get the sense of almost a chess-master behind the scenes, directing each of the characters in their complicated moves, across dance floors, across the city and across hearts. There’s a very pleasing lightness of touch, but there’s also a dark thread through the story. Not every promise is kept, either to the characters or, bravely, to the reader. It’s no wonder everyone on goodreads and Twitter is calling out for a sequel. While Kylie gives us much in Masquerade—and I hope I am not straying to close to spoilers here—there is much more left unsaid, alliances left incomplete, hearts left unhealed, and perhaps even identities yet to be fully revealed in this version of the City of Masks.

And let us not forget what lies at the heart of Masquerade—the city of Venice, in all its glory. Although in the real history of the world, Masquerade takes place in the final decades of the Republic of Venice, in Kylie’s Venice, the city is shown as perhaps the most desirable place in the world to be—for the rich and hedonistic, of course, although it has to be said that the servants also get their fair share of both the pleasures and tyrannies of this city state. But the lasting impression of Kylie’s Venice is that of a real city, and a real time and place. We don’t see a lot of historical fiction for teenagers in this country, and I think that’s a shame. Australian writers have always been excellent tellers of history, and not just of our own. And while, as I said, Kylie’s Venice is not exactly the real Venice, nevertheless, her research is both deep and transparent—you never get the feeling, as is often the case with historical fiction, that her research is showing. She’s obviously fully absorbed the ambience and the geography of the city, both from her extensive book-based research, and from her time spent there during the writing of the final drafts of the novel.

So, on every level, I commend to you Masquerade. It’s a book that shines with its respect for its young readership, but that can also, will also, is also being appreciated by readers of all ages. There are characters and stories—and frocks—to please every reader. I hope that you will all join me in congratulating Kylie and in wishing her, and Masquerade, every success in the world. Or, as the Italians would say, Buona fortuna! To which, I am told reliably by Signor Google, the response is Crepi!

So, on every level, I commend to you Masquerade. It’s a book that shines with its respect for its young readership, but that can also, will also, is also being appreciated by readers of all ages. There are characters and stories—and frocks—to please every reader. I hope that you will all join me in congratulating Kylie and in wishing her, and Masquerade, every success in the world. Or, as the Italians would say, Buona fortuna! To which, I am told reliably by Signor Google, the response is Crepi!

Buona Fortuna, Kylie—here’s to more of Orelia, Angelique and the rest of the players, and to many, many more books of all kinds in the years to come.

Crafting memory

I’ve always been primarily a fiction reader, but as I’ve gotten older, I’ve found a real interest in and attraction to memoir, and to certain types of non-fiction associated with personal stories. I’ve always liked biography, and indeed, as a young person a lot of the fiction I read (in late primary school, early high school in particular) was historical fiction about real people—Jean Plaidy‘s seemingly endless series of fictional re-imaginings of the lives of queens and princesses, mistresses and the men who loved and (too often) done them wrong (I’m looking at you, Henry Vee One One One).

These days, I mostly seem to gravitate towards memoir by writers, or other artists. I think one of the first books of this kind I really got fascinated by was Home: The Story of Everyone Who Ever Lived In Our House by Julie Meyerson.  I first heard about the book when I heard an interview with Meyerson, I think on Radio National, and it seemed to me to be exactly the kind of book I would absolutely love, bringing together as it did history, domestic architecture, and the stories of real people’s lives. Foolishly, though, I didn’t write the name of the book or the author down, and it took me quite a few years before I finally tracked down a copy. And by the time I had, Meyerson had written (and lived through the fallout of) The Lost Child: A True Story*, about her son’s drug addiction and the impact it had on the family. I have a tendency to google everything I am reading/watching/listening to—I’m a bit of a bowerbird of

I first heard about the book when I heard an interview with Meyerson, I think on Radio National, and it seemed to me to be exactly the kind of book I would absolutely love, bringing together as it did history, domestic architecture, and the stories of real people’s lives. Foolishly, though, I didn’t write the name of the book or the author down, and it took me quite a few years before I finally tracked down a copy. And by the time I had, Meyerson had written (and lived through the fallout of) The Lost Child: A True Story*, about her son’s drug addiction and the impact it had on the family. I have a tendency to google everything I am reading/watching/listening to—I’m a bit of a bowerbird of knowledge trivia gossip OK I like to research!—and so once I found Home, I started reading up about Meyerson, and so had read all of the reviews, opinion pieces and general character assassination that she copped for writing about her child in such a brutal and honest way.

So there I was, reading Home, in which the son figures (as do all of the members of Meyerson’s family, as they had done in previous anonymous columns about her family life before she was outed), pre- his drug addiction and the incredible damage wrought within that family. (Whoever’s side you take on this—and believe me, I have read plenty of arguments for and against people, particularly mothers, writing about their children, to which I will return—I think there can be no dispute that this was a family in agony, and inflicting all kinds of terrible hurt on one another, parents and children alike. The question is, is anyone—especially mothers—ever allowed to write about that stuff, or is it, as was said in Meyerson’s case, the worst of the worst possible betrayal?)

So there I was, reading Home, in which the son figures (as do all of the members of Meyerson’s family, as they had done in previous anonymous columns about her family life before she was outed), pre- his drug addiction and the incredible damage wrought within that family. (Whoever’s side you take on this—and believe me, I have read plenty of arguments for and against people, particularly mothers, writing about their children, to which I will return—I think there can be no dispute that this was a family in agony, and inflicting all kinds of terrible hurt on one another, parents and children alike. The question is, is anyone—especially mothers—ever allowed to write about that stuff, or is it, as was said in Meyerson’s case, the worst of the worst possible betrayal?)

Anyway, the point is, the act of reading Home, knowing the fate of that child and this family, was almost an act of time travel, and it added a layer of fascination, perhaps even prurience to my reading, which simply would not have been there had I picked it up the day after that Radio National interview and not five years later. I remember I kept going back to google Meyerson as I read Home, to read about those early columns, trying to probe down beneath what I was reading in Home about these people, and trying to figure out how I felt about her act of writing about her family, and trying to unpick how much of what she went through as a writer was because of her status as a mother.

The other thing about me, and about why I knew I’d love Home, quite before I knew about and quite apart from the business with her son, is that I am quite snoopy about people’s private lives. I don’t mean people I know so much—I’ve just always loved, for instance, sneaking peeks into people’s homes as I walk past. I imagine the lives going on in those lit rooms, behind those doors and in the teasing glimpses f movement behind curtains. New Orleans was a dream come true for me—not only did I adore the architecture (and the more interesting the look of the house, the more interested I am in the people who live there), but those houses come right up to the footpath, and it’s so hot and steamy people keep their doors and windows wide open. Heaven for a peeping tom tourist.

And so reading about that Home, a Victorian terrace about the same age (I thought then) as the house I had bought about the same time I read the book, and all the people who ever lived there, was a perfect fit and an inspiration for me—and a double whammy, unexpectedly, when it came to prying into people’s lives.

And yes, I did go on to read The Lost Child. D’oh. (I also toyed with researching everyone who ever lived in my house, and I may still well do that one day.)

I’ve not read any of Meyerson’s fiction, although I have copies of at least a couple of her novels. The funny thing is, I actually love reading memoir by writers, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that I have had to have read their fiction or other work to be interested.

Because somewhere along the line, when writers write memoir, it becomes about the act of writing itself. And that’s what I think I am really drawn to. Jeanette Winterson‘s (whose fiction I have, as it happens, read, and loved) Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal is a case in point. I adored this book. I kept wanting to copy out bits of it, mostly the stuff she had to say about writing—copy it out because I can’t bring myself to write in books—but I recall I read most of it in the bath, where I do a lot of my reading, and it’s hard enough to keep book, phone (got to have access to google, remember!) and cats all dry without trying to also make annotations.

Winterson’s book did attract some criticism for more or less being a rehash of Oranges are Not The Only Fruit, and of the many stories Winterson has told in interviews and so on over the years about Mrs Winterson and the terrible madness of her parenting of the young Jeanette, but for me, that missed the point of the book. Yes it was a revisiting of earlier material, but that material was cast in the light of Winterson being at that stage in her life and career where she could explicitly frame that story and that life within her craft as a writer. It’s as if her understanding of her craft and her ability to elucidate it became the palimpsest of her own work. And I love that stuff. Google-addict, remember. Research. Thwarted, perhaps, PhD student. Anyway, we’ll see.

All of which brings me to the reason I first wanted to write this post—which was to reflect on two books I have recently read. There are themes intersecting here, especially about motherhood and memoir, but also about artistry and memory.

The first book is Boomer and Me: A Memoir of Motherhood and Asperger’s, by Jo Case. Disclaimer: I have known Jo via social media for a few years now, and we’ve become good friends via Facebook, sharing war stories of a personal experience we’ve each gone through, and which I won’t go into here. And she commissioned me to write a piece for the Wheeler Centre website earlier this year, so I have a number of reasons to be well-disposed towards her book. I would also say I find it difficult to imagine how I would have responded to the book if I didn’t know Jo—quite differently, I am quite sure, which is not to say better or worse, but certainly differently. So I write the following from that position of a sort-of friend of the writer. (And yes, I have met her IRL, as the young folk say; at the recent Sydney Writers’ Festival where we shared a coffee and conversation with another online writer friend, James Tierney, who also wrote the review of Jo’s book I linked to above.)

I wanted to read Boomer and Me as soon as I heard about it, not because I knew Jo (I know lots of writers whose books I haven’t read!), but because I have a number of friends and colleagues with children with Asperger’s, and this, as well as being a teacher and someone who works with young people, has given me an interest in how the condition manifests in different ways, and how people, and families, manage. Of course, every one of those children and families are different, and a book such as Boomer and Me can only every tell that one story, but also for me, if that’s the only story it tells, then it’s not likely to hold my interest.

I wanted to read Boomer and Me as soon as I heard about it, not because I knew Jo (I know lots of writers whose books I haven’t read!), but because I have a number of friends and colleagues with children with Asperger’s, and this, as well as being a teacher and someone who works with young people, has given me an interest in how the condition manifests in different ways, and how people, and families, manage. Of course, every one of those children and families are different, and a book such as Boomer and Me can only every tell that one story, but also for me, if that’s the only story it tells, then it’s not likely to hold my interest.

I loved Jo’s book. There’s an easy and pleasing style to her writing; it’s neither laboured nor self-conscious, and for me it somehow struck a balance between intimacy and privacy. At times, I felt like I was standing in the house, watching Jo make cups of tea, or pour glasses wine of wine, navigate her son Felix’s (a pseudonym) Lego and life, as her own life is revealed to her as Felix’s condition is diagnosed. I don’t know suburban Melbourne terribly well, but Jo captures the flavour of that city, where everyone seems to live within walking, or biking distance of one another, and there’s always some bit of book business going on to attend. Because Jo works in the industry, having worked for bookshops and Australian Book Review and now for the Wheeler Centre, and dammit, Melbourne is such a hive of book folk and their goings on, and from my vantage point on the far outskirts of Sydney, it was a delight to double with Jo in her bike, peer over her shoulder as she struggled with the latest draft of her WIP, and to be her ‘plus one’ as she moves around that City of Literature.

But it’s by no means a book of book biz luvvies, either, I don’t think I could have stood that. One thing that shone for me was the school dynamics Jo captures so beautifully—the classroom and playground politics, the passive-aggressive parent who always has some complaint to make about Felix’s behaviour but cannot see her own child’s complicity in the naughtiness. The teachers, wonderful and clueless. And then the doctors and psychologists, and Jo’s growing awareness that what sets apart her boy might also explain some thing about her own family… and herself.

And at the heart of it all, this boy, this lovely boy, big-hearted and slightly off-kilter, and so vulnerable, precisely because he has no way of knowing why he’s vulnerable to over-protective parents and kids and, indeed, a world which so often doesn’t, won’t tolerate difference.

There’s a scene where Jo and Felix move back into a house where Felix’s father once lived, and Felix reconnects with Steven, the boy who lives next door, a one-time best friend he’s lost touch with since his dad moved. I confess I was terrified that Steven or Steven’s parents would no longer want this friendship, now that Felix was grown up and into his personal eccentricities—all of this in the shadow of that other parent who was so unforgiving of him. I often get that sensation of holding my breath when I’m reading something suspenseful, and this was exactly that for me. (I won’t tell you how it all pans out. Spoiler!) And I think I had that reaction in large part because of the careful way Jo structured her book.

On the surface of it, or to perhaps less attentive readers, the book can appear episodic, perhaps disjointed, but the truth is, every scene is there for a purpose, every anecdote selected to later shine light on an event, or a relationship, or an idea, in such a way that eventually the threads, which may appear silken and light on the air, come together into a subtle but sturdily made whole cloth.

So, a glimpse behind the curtains indeed, and again, a book where my personal knowledge of what came after also cast a flickering light across some of the scenes. (That’s that personal stuff I mentioned earlier that I said I wouldn’t go into detail about, but it’s there for me, and like with Meyerson’s book, changed, even enriched the way I read it. In this case, though, you can’t google it, so don’t try.)

And also keeping in mind Meyerson’s experience, I can’t help but wonder what kind of response Jo has got from her Melbourne community—not so much the book folk, or the obviously great friends and family she so warmly and unsentimentally portrays in the book, but some of the, shall we say, villains. Working with true material is always fraught, and I couldn’t help but wonder if that unpleasant mother read and recognised herself in the book, and what her reaction might have been. Thing is, people never do, do they—or if they think they do, they’re usually wrong. Anyway, it appears not, or if she has, she’s kept her reaction to herself. Let’s hope it stays that way.

And finally, a brief word about Steve Bisley‘s Stillways: A Memoir**. This time, the author of the memoir is an artist of a different kind—an actor, well-known in Australia. And who knew he could write. It’s a book I also liked very much. It captures a very particular time and place in Australia—the post-war years of the 1950s and 60s, a time of huge social and technical change, with the Bisley family living on a farm on the Central Coast, halfway between Sydney and the coal-mining town of Newcastle.

It’s familiar territory to me in many respects—I was born in Newcastle, and although I don’t remember living there, we visited friends every year from our holiday house at Macmasters Beach, a little further south than where Bisley grew up on Lake Munmorah. And he’s a bit older than me, too, born in 1950 and left school before I even started, but there’s still enough cross-over in our experiences for the memoir to ring many familiar bells with me. First of all the landscape—Bisley has a very Australian voice, and he has an easy and intimate memory of place, from the shearing sheds of his uncle’s farm at the back of Dubbo to the surfer-infested beaches of 1960s Central Coast. Also beautifully captured is the 50-50 dance, and the school social, with adults and kids alike responding to the erotic possibilities in both rock and roll and the progressive barn dance. There’s sex, or the hope of it, and death, quite a lot of it, grog and as the 60s take hold, dope. It’s also funny and wry and at times surprising in the dexterity and originality with which Bisley crafts an image or concept. He’s a writer, all right, but one obviously informed by his work as an actor, and his early passion for art—there are cadences in the language and images wrought by words that clearly come from these crafts.

And it’s a book, as so many Australian books seem to be, that interrogates masculinity; Bisley’s father comes across as not only damaged by his war experiences, but somehow thwarted in his own unrecognised desires. So, too, is Bisley’s mother. It’s obviously a deeply unhappy marriage, and the father is brutal, but it’s the relationship with his mother that lingers—her ‘closed heart’, even to her own children, but yet there is evident a clear and deep attachment between mother and son.

All of this underscores Bisley’s restless nature and his anxious desire to get out and away—and that’s where the book finishes. I can’t help but hope that we get to hang out with 16 year old Steve in Sydney, as he takes up his first job and his first love, the exciting Sue Green of the blue eyes, and eventually enters into the world of acting. Bravo—and encore!

Final note:

I expect I’ll be reading a lot more in this genre. I own heaps of memoir, particularly by writers, and I’ve dabbled a bit in the area myself, mostly, so far, on a blog I keep a little bit private. (Ask me if you’re seriously interested.) And I’m scratching out plans and ideas for a memoir of my own childhood reading set against—you guessed it—domestic architecture; the houses and places we lived. And my own mother, and father, will be in it, if it ever gets written, but I am pretty sure no-one will be pillorying me in the press for it. At least, I hope not. I mean, I don’t have anything mean I plan to say about them and after all, it’s mothers who usually cop such flack, rather than daughters, isn’t it…?

___________________________________________

*Curiously, the US edition subtitles The Lost Boy “A Mother’s Story.” And the NY Times review, to which I’ve linked, is nowhere near as harsh—not really harsh at all—on Meyerson. Perhaps that reflects a difference in attitudes towards confessionals, therapy and parenthood across the pond?

** I don’t know Steve Bisley, but I did meet him at the opening night party for this year’s Sydney Writers’ Festival. He still likes to dance.

Remembering Nestlé Write Around Australia

I’ve had a lot of terrific jobs over the years, and one of the nicest was working on the Nestlé Write Around Australia creative writing program for kids. For those of you who don’t know it, it was a national program for kids in (equivalent of) Years 5 and 6, that involved sending authors to 50 regional centres across Australia, where they gave creative writing workshops to local schools, based at the public library, and a master class to the kids from that zone who were finalists in the competition component of the program.

I worked on the program from 1999 to 2001 (when I received my Churchill Fellowship from The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia and headed off overseas for 4 months). My job on NWAA was to develop teaching support materials for the delivery of the program in schools, and I also selected the books for the prizes. It was run by the State Library of NSW and I worked with the program coordinator Val Noake, who ran the program for nearly its entire life (except for the initial establishment phases, under the late and much missed Marion Robertson) and Virginia Mason. We were a good team, and it was a fun job—and I can tell you I learned more about Australian geography than I ever imagined possible!

I imagine the number of kids that went through the program must number in the tens of thousands. A lot of the stories are held in the collection of the Mitchell Library at the State Library of NSW, but, like many of these kinds of programs and jobs, you never really know what happened to those kids, even the ones who won.

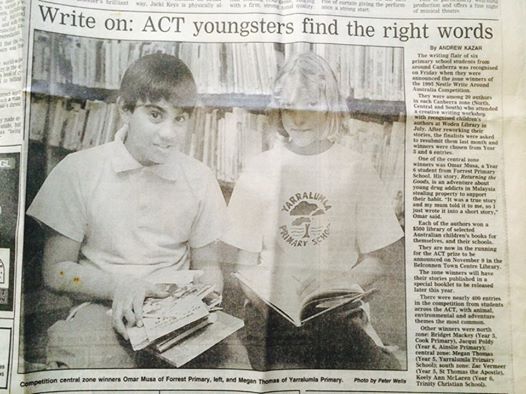

So imagine my delight to see this photo posted today on the page of my Facebook friend, writer and poet Omar Musa. Turns out Omar—whose novel Here Come the Dogs is soon to be published with a blurb by none less than Irvine Welsh—was one of the first finalists in Nestlé Write Around Australia, way back in 1995.

Omar tells me that Allan Baillie took the workshop he attended, and that he was very encouraging—I’ll be sharing this with Allan, who I am sure will be thrilled. How wonderful, though, to have discovered that one of the Nestlé kids has gone on to be such a highly regarded writer. You so rarely see this kind of follow through in my line of work (even though I wasn’t actually working on the program when Omar was involved), and this has really made my day.

I have no doubt that Omar would have become a writer anyway, but I also believe that the knowledge and experience that Allan shared and the encouragement, support and guidance he gave was no small part of that journey.

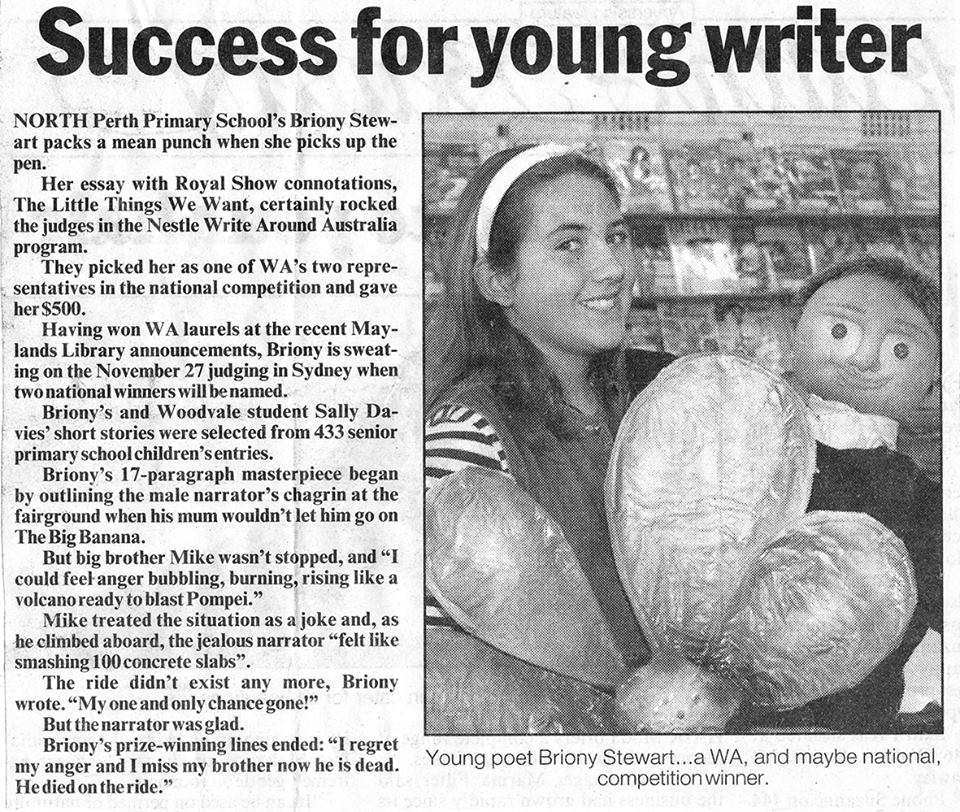

And when I posted this on my Facebook page, author-illustrator Briony Stewart left a comment to say that she too had been a NWAA finalist, a year after Omar, in 1996.

Which makes me wonder—how many more of our finalists went on to become writers? Please leave me a comment here if you know of any!

It all serves to remind me—the work I (we) do is important, and it does change lives.

Dear Mr Pyne

I am sure anyone who knows me or reads this blog has a pretty fair idea of where my political and ideological affiliations sit. I won’t go on in length here about the recent budget or the horrors of the past 8 months under this LNP government… that’s what Facebook and Twitter are for, after all.

But I did want to share the letter I just sent, via the Australian Greens Senator Penny Wright’s petition regarding the government’s reneging on their repeated promises that they would honour the Gonski report recommendations, and match the level of funding promised by the previous Labor government. So here it is.

Dear Mr Pyne,

I was deeply concerned to hear your public statement that you and your party are ’emotionally committed’ to private schools.

As Federal Minister for Education, you should be emotionally committed to the best outcome for every student in every school in this country, and as the person responsible for the allocation of tax-payer funds, that should primarily mean students in public schools supported by the Australian public through our taxes. Australia has a justifiably proud heritage of free universal education for every student, a heritage based on the philosophy of pioneers such as Sir Henry Parkes, who had a vision for public education where every Australian child would sit ‘side by side’ and have full educational access and equity regardless of their social or cultural background.

Australians have overwhelmingly demonstrated their approval of the reforms proposed by the Gonski report. You stated repeatedly before the election that schools would receive the same amount of money under your government as promised by Labor. Please honour your word and honour the children of Australia by reversing your decision to abandon the reforms and funding you promised.

I have spent nearly my entire working life working with and for children in some of the most disadvantaged areas of western Sydney—the very region most pandered to by unfulfilled promises from your government. I have seen first hand the difference a properly resourced, well-maintained school can make in the lives of these children. The much-maligned program of new school facilities built by the previous Labor government has provided these schools with dedicated library spaces (not leaky demountables) where children may read, research and study; school halls that have freed up spaces in the school to allow creative arts, sports and other rich engagement programs that most benefit the most disadvantaged. Money may not solve every problem in our schools, but the lack of it creates many, many more.

You may be emotionally committed to your old school tie, and the benefits that have flowed your way from that privileged community. I am emotionally committed to ensuring that children who did not start out in life with the advantages you did have at least some chance to make the most of their potential, and that’s where I want my taxes to go.

Fund the Gonski recommendations in full. Anything else is truly a false economy.

Yours sincerely,

Judith Ridge

From the Vault: Alice in the Undertoad

From misrule.com.au/s9y

Originally published Saturday March 6 2010

________________________________________

I went to see Alice in Wonderland last night.

As some of my readers will know, Alice is one of my favourite books. I have a smallish but nice collection of different editions of Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, as well as another small but interesting collection of Alice-abilia/-iana, whatever you call it. (China, characters in different media, including a set of Beanie Babies of the Disney cartoon versions of the characters, 1920s toys, etc etc. Also Carroll-iana—I’m sure I’m making these words up!—collections of his photographs, biographies and so on. I should photograph the collectins and post it for those interested.) I’m not unusual in that regard: Alice is held dear by many of my friends in the children’s book world, and I wouldn’t say I’m any more of a fan than many, and less than some. But I thought it was worth mentioning as I am about to discuss the film: Alice figures large in the history of my reading life, but I am by no means a purest when it comes to adaptations or interpretations. I’m always interested to see what artists see in the books, which is why my collection focuses on illustrated editions across the past nearly 100 years. I don’t think I’ve really seen a straight filmed version of the book that I love, but nor do any offend me mortally. (I just don’t watch the Disney cartoon one, makes life very simple!)

So there you are: my personal context for seeing the film.

I should also say that I am generally pretty open-minded about film adaptations of books. I guess I tend to view them as very different experiences, and I go to see a movie and hope it is a good movie in movie terms—I don’t expect to see the book replicated on screen. That said, I do think it’s possible to completely ruin a book, and that’s usually the case with movies “adaptations” when you see the film and think, why did they even bother to pretend that it was based on the book. Or adaptations which so egregiously misrepresent important elements of the book—such as the race of the main characters—that I get as outraged and upset as the next person. But if a film makes a fair stab at adhering to the emotional truths of the book and don’t play fast and loose with its politics, I am usually OK with it.

And having said all that, Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland is not, of course, an adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

I didn’t realise that when the first trailer teaser was “leaked” on the internet. I assumed it was going to be Burton’s vision of the book, but it’s not. Well, not exactly. Instead, as I was more or less relieved to discover, the film was to be set several years after Alice’s adventures in Wonderland, when she is 19, and apparently escaping an unwelcome marriage proposal. I have to say the sound of the engagement plot didn’t appeal much (and it turns out that it still doesn’t appeal, now I’ve seen the film, but more of that later), but I didn’t mind the idea of the movie being Alice’s return, especially given Hollywood’s penchant for adding years to a protagonist’s age for the sake of “audience appeal” (read: The Twilight Effect). What I mean is, if they were going to cast an adult actress, then for heaven’s sake don’t pretend she’s 10, or worse, update the book to match her age. So on that count, the “sequel” idea sort of appealed, and in any case, I was interested to see what Burton would do with this “Return to Wonderland” approach.

For me, what he did—and I know that comparisons are odious, and I actually generally really love Burton’s films, so forgive me—but for me, what he did was give us a bit of a mashup of Narnia (with the Red Queen stepping in for the White Witch via a slightly mean caricature of Elizabeth 1) and a NorthernLights/The Golden Compass Lyra-esque prophecy with a dash of BBC costume drama (I’d say Austen but it’s about 40 years too late…), all with a modernish feminist(ish) sensibility.

And I don’t mind any of that, really. It just kind of seems… beside the point. The frame is pretty silly. The lost father stuff works OK motivation-wise (as my friend Monica points out at Educating Alice, her blog which is, of course, named for Carroll’s heroine), but the engagement stuff is pretty silly. The potential fiance is so utterly repugnant, and why on Earth would his stuffy mother be so keen on the engagement if the family business has gone bung? We don’t know who Alice’s sister is until an utterly spurious scene in which Alice finds her brother-in-law kissing someone else in the hedges, which is, and remains, apropros of absolutely nuthin’, and is a very silly modern addition in any case. Simply put, the frame adds nothing thematically to the main story: it neither adequately reflects nor expands on the main themes of the film, and as such, is more or less pointless. I was, however, glad to see Lindsay Duncan and the sublime and under-utilised Frances De La Tour (although as Bonham Carter herself has pointed out, Burton makes no concessions to an actress’s vanities!).

Someone in the group I saw it with said she kept waiting for the actors who played characters in the frame scenes to pop up in Underland (which is apparently its real name, misheard by the child-Alice—I actually quite liked that innovation). Apart from two non-identical twins who were meant to echo Tweedledee and Teedledum, this doesn’t happen, and I’m glad of it. I think it’s a weak point of the film of The Wizard of OZ, having characters in OZ played by the same actors as Dorothy’s friends and family in Kansas, suggesting as it does that it was, after all, “just a dream”. (I’m sure this is original to the film, but I haven’t read the book since 197-gulp, so someone will have to remind me if I’m wrong.) I liked that W/underland is real and that Alice THOUGHT it was a dream, and I’m glad she gets to remember it at the end. (I did think, for a moment, though, that Dorothy’s red shoes might make an appearance… if you’ve seen the film, you may know the moment to which I refer.)

In fact there was quite a lot I did like about the film—Johnny Depp, who is always worth watching, makes a terrific Hatter, as expected (and what did everyone else think of the use of the raven and the writing-desk riddle as a sort of refrain between him and Alice?). Anne Hathaway as the faux-affected White Queen was very amusing (and I don’t think Wonderland is going to be all that better off under her rule rather than her sister’s, actually!). Alan Rickman’s sinuous voice for the Caterpillar was marvellous (although I am still a bit puzzled why so many of the characters got names—the Caterpillar is Absolom, amongst others, and I don’t geddit…) I was a bit disappointed in the Cheshire Cat (despite my eternal adoration for Stephen Fry), not sure why, and the poor White Rabbit was reduced to a cowardly wreck, which he’s not. Bonham Carter is fine as the Red Queen, and comparisons to Miranda Richardson’s “Queenie” in Blackadder are, I think, unfair if inevitable. (Bonham Carter’s Red Queen does owe a great debt to the historical Elizabeth I, though, I would say, especially as far as ERI’s penchant for favourites is concerned. And didn’t Miranda Richardson once play the Red Queen? Oh yes, here it is—Queen of Hearts. Hhmmm… now I’m confused. Is Bonham Carter’s character the Queen of Hearts from Wonderland or the Red Queen from Through the Looking Glass or an amalgamation of the two? Curiouser and curiouser!)

Mia Wasikowska is a wonderful young actress, as anyone who saw her in In Treatment will know, and she’s perfectly fine in this role. She’s not the Alice we all know, of course—her Alice is a rather worldly young woman, not Carroll’s “dream-child”—but a completely original character who better suits the modern, feminist sensibility I mentioned earlier. Whether or not any of that works for you?—well, tell me in the comments.

The film has Burton’s characteristic “look”, and at times I did find it a bit on the dark side (actually, not metaphorically, although that too—the heads in the moat bringing to creepily literal life the Queen’s trademark cry “Orf with their heads!”) and I also found it quite hard to hear what people were saying at times. (Most of those afore-mentioned new character names were lost on me. And again, I think they were unnecessary.) It was Wonderland meets Corpse Bride via Coraline as far as the set design goes, which I guess is to be expected (although I note that Burton was not involved in Coraline, but its director, Henry Selick, worked on The Nightmare Before Christmas with Burton).

But frankly, I’d rather have seen Burton’s take on the original Alice story. He clearly knows it intimately, or his screenwriter does (the detail of the film proves this), and has an empathy with for its darker, surreal moods, so why not just let him have his not inconsiderable head with Carroll’s world and see what he came up with? Alice doesn’t need modernising—she’s a girl for the ages, as so many pre-adolescent heroines of children’s literature are, from Alice through Anne Shirley and Judy Woolcot to Lucy Pevensie and Calpurnia Tate—before puberty and the imperatives of potential womanhood begin to hit home.

So no, I didn’t hate it. I liked a lot about it. I’ll see it again (I didn’t see it in 3D and actually, I feel absolutely no desire to) and probably buy the DVD. It’s not terrible, but we’re still waiting for an imagination to match Carroll’s to really bring Alice to the big screen.

Whither the Children’s Book? From the Vault: Wednesday, June 15 2011

This post was first published in June 2011, but it’s as relevant as the day I wrote it. Just this weekend, in fact, I read a review which described Neil Gaiman‘s Fortunately, The Milk, as being for ‘the younger end of the YA readership’. Um, no. That would be CHILDREN. Remember them? They’re not mini-teenagers. They’re children and so there are children’s books and let us not forget it. Anyway, here’s my rant from 2 years ago. Consider it current.

______________________________

I first used this phrase (Whither the Children’s Book?) in my blog post about this year’s (2011) Sydney Writers’ Festival in context of the panel I chaired on the young adult/adult cross-over novel that was, rather ironically I thought, called “When is a children’s book not a children’s book” (ironic, because it wasn’t about children’s books at all). This is what I wrote:

given the title, I also brought in the question of Whither the

Children’s Book in a world when YA and the cross-over gets all the attention

but to be honest, we didn’t really answer the question. I think, from memory, we all kind of agreed that children’s books don’t get much attention and then moved on to questions.

Because not a lot seems to be about the children’s book, these days. The children’s novel, to be precise. YA gets vastly more of the blog space, media attention and arguably, reviews—although the picture book probably gets a fair bit of review space as well (and Shaun Tan’s done a hell of a lot to make the picture book an acceptable topic of conversation in adult society). And increasingly, I’ve noticed that when a children’s novel does get critical attention, it’s suddenly claimed as being young adult.

It happened to The Graveyard Book. It happened to When You Reach Me. And these are both classics examples of children’s literature, as far as I am concerned. I’ve argued the toss on this online and elsewhere, especially about The Graveyard Book, which people seem to want to claim as YA primarily, I think, because it deals with death and because of the extremely scary opening scene where the family is murdered (oh shut up, that’s not a spoiler). My argument about The Graveyard Book is this: it ends at the point where most YA takes up: Bod has to leave the graveyard to find his agency, and we don’t get to see that process. The rest of the novel—Bod finding who he is in the context of the only family he knows, through adventures that are often perilous, coupled with the exploration of friendship—is the classic stuff of the children’s novel.

The claim for When You Reach Me as YA puzzles me even more. Thematically, it shares nothing in common with the typical YA novel, but is firmly in the tradition of the great children’s novels—Harriet the Spy, A Wrinkle in Time. Andre Norton‘s Octagon Magic springs to mind for some reason. I’m also thinking of The Game of the Goose and the lesser known The Games Board Map—children’s novels with a puzzle to be solved at the heart. There’s no subtext of the achieving of subjectivity, such a classic feature of the YA novel. These are all novels about children, with the concerns of children at their heart—friendship and family and belonging and home.

(For the record, I had a conversation about this with Rebecca Stead at Reading Matters last month, and she is firmly of the opinion that she writes children’s novels—and she says the letters she gets from her readers bears this out. So there.)

The only thing I can put the claim for such books to be YA down to is this—that they are books that are literary, meta-textual, substantial books full of ideas and complex plotting. They’re books that need time to read and consider and digest—books that take, as a frustrated parent of a frustrated 12 year old reader once said to me, longer than an afternoon to read. But complex doesn’t ergo mean older.

It’s as if we’ve all forgotten what kind of books we read as children. It’s as if the whole rich heritage of 20th century children’s literature has become some kind of quaint historical anomaly. It seems to me that the huge emphasis on writing and publishing books for “reluctant readers” (often code for “boys”) over the past 20 years has pushed the classic children’s novel so far out of our collective consciousness that we don’t even recognise it when we see it any more. If it’s longer than 200 pages, if it has serious ideas and challenging language, it has to be for young adults—almost seemingly regardless of the age of the protagonists and the thematic interests of the story. And it bothers me enormously that the gifted, devoted, passionate child reader doesn’t seem worthy of our attention any more.

Why am I banging on about this all of a sudden? There are two reasons: first, a long-standing concern and second, something I read today that really got up my nose. Here’s the first: the second will come right at the end of this post.

Reason for Banging On the First.

Well, first of all, the near-demise of the children’s novel, in this country at least, has been a concern of mine for more than a decade. It’s not just that YA is sexy and dark and dangerous and so excites the blood of the “won’t someone think of teh children” brigade (and yes, I get the irony that here they’re actually NOT talking about children at all, but treating young adults as if they WERE children) and so gets all the media attention. (No, I will NOT link to the notorious Wall Street Journal article; that damn woman has had far more than her 15 minutes of attention and I won’t be party to giving her a second more. And if you don’t know what I’m talking about, google WSJ and dark and young adult and you’ll find it. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.) It’s more that the categories—children’s and young adult—seem to have been pushed so far apart from one another, in awards in particular, that there seems to be this huge gaping space into which the children’s novel, as we have known and loved it for about 150 years, has fallen.

If you’re not sure what I’m taking about, go to the Children’s Book Council of Australia’s website and compare the shortlists for the Book of the Year Award either before there was a split between Older and Younger Readers categories, or even in the early years of separation of the age categories. Look at the books shortlisted in the 60s, 70s and even 80s for the 8-12 year old reader (what the Americans usefully call “middle school”) compared to the Younger Readers shortlists of the past 10-15 years. Note how these days, there’s only one or two really substantial novels for this age (what I’ve always thought of the “golden years” of reading), with the rest of the shortlist made up of short, illustrated chapter books, typically for the under 8 years olds, and even picture books.

I’m not saying that those other books, the chapter books and more sophisticated picture books, are bad books or should not have been selected as books of merit—I just look at those lists and wonder where are all the great novels for children? Isn’t anyone writing them any more? Or is no-one publishing them any more?

Over the years, I’ve heard different views on this from Australian publishers. A decade ago, they were telling me they weren’t publishing them because they couldn’t sell them—apparently schools and libraries wanted the inheritors of the Paul Jennings phenomena; Aussie Bitesand books with a wider market appeal—and it wasn’t economical to publish literary fiction for that age. So the readers, like the child of that parent I mentioned earlier, who I spoke to when I was working in a children’s book shop who said he his daughter needed books that lasted longer than an afternoon—those readers either had to buckle down and read more mature fare that they weren’t really ready for, or stick with the classics, or read books from the US or UK, where they still seemed to be publishing real novels for the devoted child reader.

More recently, they tell me that the problem is that writing a really great children’s novel is incredibly difficult, and they just don’t see the quality manuscripts. Australian publishers tell me this; and Amanda Punter, the Penguin UK publisher on that Sydney Writers’ Festival panel, said it too. I just remembered! Yes! That was pretty much the answer to my question—Whither the Children’s Book? It’s hard to do well, and we’d publish more if we saw more of them.

Maybe that’s true—I suspect there is some truth to it. I can’t imagine the level of gift it would take to write a Hazel Green novel or a Tom’s Midnight Garden. But it’s an odd argument at the point that once upon a time there weren’t really any YA novels and plenty of wonderful children’s novels—has it somehow become harder to write a great children’s novel, or have writers turned their attention to other audiences?

What I am sure is true is that there are vastly more books published for young readers now, a greater variety and indeed, I’ve argued that there are more books for different kinds (and abilities) of young readers than ever before, and that’s a great thing. (I made that point in answer to a question at the Sydney Story Factory panel on children and writing at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, and I think it’s true.) So maybe it’s just that there are more books vying for incrementally less and less attention (see another recent post where I mentioned the shrinking of book review pages across the board in mainstream newspapers and the like).

But I can’t help but think that there are fewer contemporary children’s novels of the type you and I grew up devouring, and that’s emphatically not a good thing. And to circle back to my previous point, for some reason when we do see those books, they somehow get shanghaied as young adult. Which they’re just not. Which brings me to:

Reason for Banging On the Second.

This blog review of Oliver Phommavanh‘s second (and very wonderful) children’s novel Con-Nerd, in which our goodly blogger describes this book and others of its ilk as “young-young adult”.

Yup, you read it right. “Young-young adult.”

Is that really what we’re calling it now?

Heaven help me.

I don’t mean to have a go at you, goodly Alpha Reader blogger, but for god’s sake. It’s not “young-young adult”. There’s no such THING as “young-young adult.” It’s a children’s novel. A novel for children. There are still children in the world and they still need novels.

So maybe, after all, I am saying, will no-one think of teh children? But more than that—will no-one think of teh children’s book?

We can’t all be Miss Honey and maybe we shouldn’t even try.

I got a little bit cranky on Twitter tonight.

Oh, that’s nothing unusual. Twitter is kind of designed to make you cranky—indeed, that’s why many people, it seems to me, seek it out. Me, I usually retreat when I start to feel my blood pressure rise. Emotional equilibrium is pretty precious to me, and I’m not a great fan of conflict at the best of times.

But sometimes those cranky-making conversations are good for you. They get the old blood flowing to the head, and start to make you think about things, and why they get you cranky, and what you actually think about the topic beyond the initial instinctive reaction. And that’s brought me here.

The discussion was started by a tweeted report of a comment made at a conference where the speaker apparently said something about how schools kill off a love of reading, or make kids hate books, or something like that. It was a conference about YA literature, so presumably they were talking about teenagers, which means they were talking about high schools, which means, let’s face it, they were talking about English teachers.

So I hit the sarcasm hashtag and made a reply tweet about idiot English teachers whose ambition in life is to turn kids off reading, which in turn brought out all the (entirely anecdotal, of course, and so entirely unprovable of anything except themselves) comments about English Teachers Tweeps Have Known who don’t read. Apparently there’s a plague of them. Which of course proves the point that the main purpose of the English classroom is to make kids hate reading too.

What really stuck in my craw was that these tweets were mostly coming from teacher-librarians.* I made my own observation that I knew teacher librarians who didn’t like fiction OR students in equal measure. I was unlucky enough to teach in a school that had two such nightmares in rapid succession—well, one liked fiction OK but my GOD she hated the kids. Terrified of them, actually, which amounted to the same thing. Which anecdote is only useful insofar as it proves that there are probably, by extrapolation, at least some other TLs out there who similarly don’t see it as their job to even loan books to kids, much less turn them all into card-carrying members of the Puffin Club, but that doesn’t make them representative of the profession as a whole. Of course.

I mean, maybe it was just a bit of territorial pissing, but the fact is, I really find these kind of comments about fellow teachers, whoever they come from, and whatever the actual content of the criticism (work in a school long enough, ie five minutes, and you’ll hear every kind of cross-faculty bitching you can imagine) the educational equivalent of the Elaine Awards. You know—the award named for the late Elaine Nile for Comments Least Helpful to the Sisterhood.

I mean, really, teachers don’t have enough shit to put up with that we have to go on line and publically bag one another’s professionalism?

And I say ‘we’ even thought it’s well over 20 years since I taught full time, and ten since I spent any time ducking spitballs and fake names in roll call as a casual teacher, but the old adage is true—once a teacher, always a teacher. I am as passionate today about the profession as I ever was, perhaps in some ways even more so because I know how hard it is and how hard it is—especially when half of that is because of the criticism that is so freely and so frequently thrown at teachers—is why I left.

And another reason I left, although I don’t think I ever actually articulated it this way when I hung up my dust jacket (kidding—I never wore a dust jacket, although it is so long ago that I taught that I still used chalk)… One of the main reasons I left being an English teacher was because I realised that it was not my job to make kids love reading.

Let me say that again.

It is not an English teacher’s job to make kids love reading.

To think it is, is at best naïve innocence (the kind all first year out teachers should probably have to some degree); hubris at worst.

Ask yourself this: What other subject do we expect teachers to make kids love? Do we expect maths teachers to make kids want to race home and do a few algebraic equations for the fun of it? Do we expect geography teachers to inspire kids to go on walks on the weekend in order to map the topography of the local neighbourhood? Do we think history teachers have failed at their jobs if kids aren’t conducting archaeological digs in their back yard or dragging their parents off to a Historic Houses walking tour in their spare time?

And those of us who hated sport with a passionate hate—we bookish types who resent being shifted from our cosy position under a rug and a cat—how much did we loathe and despise the evangelist PE teacher who ran 1st double period on Friday like a compulsory exercise yard in a Beijing factory? Did they fail at their job because however many years or decades later, we’d rather poke ourselves in the eye (OK, not that—we need those eyes for reading) than go for a jog?

But English teachers, it seems, carry a particular burden. Despite the fact that’s the only compulsory subject right through to Year 12, so every single child who goes through school, be it in a bricks and mortar jobby, a home school or via correspondence or School of the Air, has to study English. Every child, regardless of intellect or inclination. And yet somehow it’s the English teacher’s job to make them all avid under-the-cover, couldn’t-think-of-anything-else-I’d-rather-be-doing, readers for pleasure.

Well, it’s not. For a start, it’s a ridiculous, unrealistic and again, arrogant goal to think that every single child could or should love to read for pleasure (by which, I should add, we almost always mean fiction). I’m not talking about being able to read, and at more than a simple able-to-decode standard; the necessary literacy skills to more-than-survive in a modern, complex world. I’m talking about reading for pleasure. It’s just not the English teacher’s job to make people love reading. And I can tell you that for those of us who think it is, that way frustration and disappointment lies.

I wanted it to be my job as an English teacher—to make kids love reading— although I didn’t consciously realise it at the time. I wanted it to be my job because that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to make kids love reading the same way I loved reading. More than that, I wanted them to love literature in the way that I do. And sometimes I was successful—I was great at book talking, and I always had kids keen to take home the books I recommended to them, just as if you speak enthusiastically to a friend about a movie you’ve seen or a place you’ve been to, they’re likely to think they want to see it, or got there too. Doesn’t mean they will, of course, although they might wish they had in a kind of half-hearted, if-only-I-didn’t-have-something-better-to-do fashion.

Sometimes those kids did read the books I book-talked, and the memories of some of those kids and books remain my most vivid from my teaching years. But probably most of them, in the end, didn’t. Or maybe they did, and enjoyed them well enough, but not enough to come back to me after the weekend and demand ‘another one just like that’ (one of those treasured memories). In other words, I may have encourage them to read and enjoy the odd book, or at the very least think that reading for pleasure wasn’t just a completely oddball thing to do, but for most of them I daresay, if they weren’t already interested in reading as a leisure activity, I doubt my enthusiasm converted them. And that’s OK.

Because not everyone has to love reading. Everyone should be exposed to good books, so as to have the option, just as everyone should be exposed to science and maths and sport and cooking and woodwork and music, but not everyone can possibly ever hope, or be hoped, to love maths or music or making muffins.

But don’t I think people’s lives are better if they like to read? Well, no. I can’t in all honesty say I do. I think people’s lives are immeasurably worse off if they CAN’T read, of course, but it would be a huge disservice to the millions of people world wide who either by choice or by circumstance don’t read for pleasure, and live perfectly well-adjusted, fulfilling and meaningful lives. Who am I to say, oh, but you’d be so much better off if you just read this novel! Who am I? Some self-important English teacher, that’s who I’d be. And that’s why I’m not an English teacher any more—because I wanted to say that and It Wasn’t My Job.