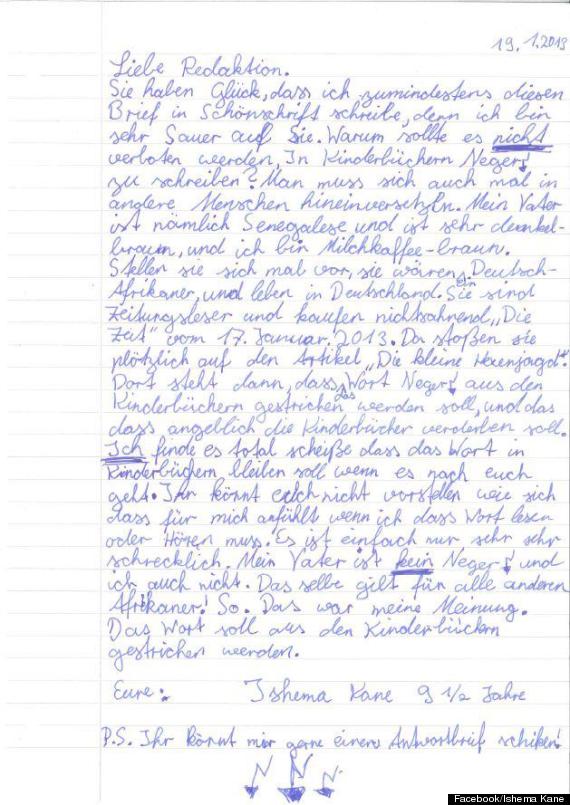

There’s a story on the Huffington Post today about a young girl, Ishema Kane, in Germany who wrote to the newspaper, outraged at their defence of racist language in children’s books—specifically, Pippi Longstocking. As letters of outrage go, it’s pretty fabulous. I especially love this bit: “I find it totally shit that this word would remain in children’s books if it were up to you.” You go girl! (She’s only 9.)

(I also note that the N word under scrutiny is apparently ‘Negro’, not the other N word, and am interested that this word appears in this instance to have caused as much distress and impulse to censor as the other, more commonly offensive N word. However, that’s a slightly tangential point to what I want to address here, but if anyone has any thoughts on that, please share.)

Now, this is not the first time this topic has raised its head in children’s literature circles, not by a long shot, but I posted the story on Facebook and it engendered very interesting discussion that I thought I’d bring over here to the blog.

But before that, let’s have a bit of an overview, at least from my point of view, of how I’ve experienced this debate. I think it first raised its head for me back in the 90s when the Billabong books were reissued with the more, by contemporary standards, offensive language and attitudes towards Australian Aboriginal people removed. Sanitised. Censored. Depending on your point of view. (And look! I wrote about this back in 2006!)

The child_lit community has debated this topic many, many times over the years, particularly as it relates to portrayals of Native Americans (the list being US-based and mostly made up of US children’s lit professionals and enthusiasts). The discussion has often been spear-headed by the women behind the Oyate site, which provides reviews and resources on books by and about Native Americans—and doesn’t pull any punches when it finds books and authors it finds objectionable. (See also Debbie Reese’s blog American Indians in Children’s Literature.)

These discussions on child_lit sometimes became very heated, especially when heart-held favourites, and strongholds of the canon—such as The Little House on the Prairie—were cited as books that could, had and continued to cause great hurt to Native American children who come across, or worse, are forced to read the book in school (because if you come across it yourself, you can chuck it across the room. If you have to read it for school, not only do you have to read it, but its very place on the reading list gives its attitudes and language an imprimatur).

I don’t know that Debbie Reese and her colleagues were arguing that bonfires of the Little House and Little Tree books should be lit across the land, much as maybe they privately wished that to be the case, but they were (are) determined to continue talking about this issues, difficult as it is for all of those of us who held Laura and Pa and the Billabong gang so close to our hearts as we grew up, then and now.*

My idealised view has long been that if the books hold values that are so anathema to contemporary values, then the books should be allowed to quietly disappear into the archives. I’m not a fan of tampering with a writers’ work/words/intentions, especially when they are not around to contribute to the discussion/editing process, no matter what the Estate might have to say about it.

But of course, it’s not as simply as that. Books don’t just quietly go away. First of all, what’s to stop people, even children, coming across them in secondhand bookshops, or in libraries with a conservative culling policy, or on the shelves at Grandma’s house. Perhaps more potently, though, there’s the nostalgia value: parents, aunts and uncles, grandparents and teachers who want to share beloved books from our own childhood with the kids in our lives and classrooms. Sometimes we’re shocked to find what lurks in those beloved pages, and maybe we think twice about passing them on, or maybe we excuse those transgressions away with the argument that those attitudes are from another time when people didn’t know better. (Except that they did.)

There’s also the cultural argument: many of these books have stood the test of time, and still are popular and have much to offer readers now. Do we throw the baby out with the bathwater—you can read 6 of the Narnia books, but not The Horse and His Boy. (Or, arguably, The Last Battle, especially if you want to add sexism into the mix, but I think it’s fair to say that people get more upset about racist attitudes in children’s books than archaic sexist attitudes. I’m not sure why that is and don’t have time to think about it right now, but I’m keen to come back to it at some point.)

So if we operate on the assumption that most of us are pretty much bottom-line against censorship, as in outright banning these books, and we accept that these books aren’t likely to just magically disappear on their own account, what are we left with?

We reissue them with changes to language and attitudes—mid-range censorship. Or we let them stand as they are, reader beware. Treat them as a learning opportunity. Do Not Whitewash the Past. But at what cost?

As I said, I posted the German story on Facebook, and the first response I got was from my friend Gayle Kennedy, a wonderful writer for adults and children, who is a a member of the Wongaiibon Clan of the Ngiyaampaa speaking Nation of South West NSW. Gayle’s not backward in coming forward in expressing her opinions on, well, anything, so when she just posted a quizzical ‘Hhmmmmm…’ in response to the post, I was curious to find out what she REALLY thought.

I don’t like people fucking with other people’s writing. Simple as that for me. I can’t bare what’s being done to the texts of yesteryear. How are you going to learn from the past (mistakes and all) if you keep sanitising it? Sanitising these book means that kids these days do not have the benefit of seeing how far society has come in terms of how we see other people and society in general. Why not point out to the kids that these words and terms were used all the time in that day and age and how society has grown and realises now the harm and hurt it caused and still causes. There are lessons to be learnt from confronting these texts head on and none of from running away from or excising them.

*I’ve personally never actually read a Billabong book, and while I read the Little House books as a child, it was the TV show that won my heart. As the name of this blog attests, my best-beloved childhood book of this kind was Seven Little Australian Australians, which actually had a passage sympathetic to Aboriginal people removed after the first edition, not to be restored for 100 years.

Such a loaded topic, and so important. I don’t think there’s a correct answer. It’s something that I deal with on a regular basis. This year I translated “The 101 Dalmations” and was shocked by the blatant sexism, which I had not remembered, and classism, and racism (towards gypsies). Also very Christian values, to the point of alienating non-Christians. Here and there expressions could be softened in translation, and I deliberated whether it was my right to do so? My duty? I wrote a translator’s afterword addressing some of these issues but the publisher objected to the afterword, saying that I was overly critical and it seemed that I hated the book. But I don’t, I actually really like the book, and it has many fine qualities. Just one of many examples that come to mind.

It’s a really difficult issue. I’m totally against censoring the author’s original work, but at the same time I know I was guilty of some verbal editing when reading some old stories aloud to my child when he was little. As he grew older, we could discuss the more uncomfortable aspects of certain old classics. But not every child will have parents who will do that.

I think the only ‘answers’ are to allow the books to fall into obscurity or, if the book is considered too important for that, produce contemporary versions with explanatory notes for today’s kids. However, both ‘answers’ look unlikely right now, with digital versions of out-of-copyright books available for free.

While I was reading some Enid Blyton to my children at home I used it as a good opportunity to discuss attitudes towards girls and women back when Enid Blyton was writing and attitudes now. While the immediate benefit of this discussion was to draw their attention to a particular issue in the book we were reading, these types of discussions also encouraged them to question what they were reading – an attitude towards reading that they could apply to other books. However, I also avoided introducing to them those old books that I thought had transgressed too far.

The arena I think you are particularly concerned about is the school classroom. I think this is different to the circumstances of a home. Group dynamics come into play and the teacher cannot spend intimate moments with every child in the classroom. The teacher has a more difficult task in managing the reception of such books.

There is so much good quality children’s literature that a teacher can draw upon why choose a book which uses negative stereotypes when depicting certain types of people? There is no need to edit such books, just don’t use them in the classroom.

I am not in favour of editing negative references out of a book. You are right that a child might stumble across such a book in a second hand book shop or on Grandma’s bookshelf. My scenario relies on the parent to have a discussion with their child about the books they read. Not all parents do this. Thus it is important that teachers do teach regularly about the importance of treating people fairly and equally, that negative stereotypes and prejudice harm our society.

Changing a culture is hard work and doesn’t happen overnight. There is no perfect solution to the quandry you present here. We need to be tenacious in our quest to eliminate prejudice and tackle the issue from many directions.

Pingback: To Change or Not to Change, That is the Question | educating alice

Good morning, Judith,

As I write, it is 4:30 AM in Illinois (I’m an early riser). My first thought each morning is of my daughter. She is miles and miles away, in the UK, working on a master’s degree. She and her cousins are the driving force in what I do at American Indians in Children’s Literature. Five of her cousins dropped out of school. Two graduated. One is in 8th grade.

Beginning in pre-school, we encountered stereotypes in the books her well-intentioned teachers read. She is a smart girl (graduated from high school at 16 and went to Yale), perceptive, and would, in a gentle voice, object to stereotypes. Because stereotyping in children’s books was my research, books with them were all around our house. She’d see them, of course, and I’d tell her what was wrong with them. One time, her pre-school teacher was going to read BROTHER EAGLE SISTER SKY. She told the teacher it wasn’t right, and, the teacher said “but it isn’t about your people” and told her she could go play instead of participate in that day’s read-aloud session. That was the first of many, many episodes.

Because she is exceptionally gifted and had/has our support, she’s persevered through all of that, but she’s definitely an exception. The drop out rates for Native children are astonishingly high, as the experience of her cousins demonstrates. Researchers who looked at this recently put forth the idea that one reason for dropping out is that the student disengages from school because year after year they are not given accurate portrayals of Native people. Instead, they encounter misrepresentations and bias. I’ll say that again: year after year.

We (here in the US) or there (AU) can (and should) stand by freedom of speech and creative license, but it doesn’t mean we must insist on keeping racist texts in the classroom, especially when doing that may be a factor in pushing a child in your classroom towards dropping out. As you note, there’s so many other good choices.

Just read a related story in the NEW YORK TIMES: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/31/books/releasing-old-nonfiction-books-when-facts-have-changed.html?_r=0

The TIMES piece is about an old work of nonfiction being reissued in digital format. Facts in it are now known to be incorrect, but the publisher issued it without comment. Last year I wrote about a book I found in the local library. It is an encyclopedic sort of reference about American Indians first published in the 1950s, and republished a few years ago without any updating at all. It definitely needs to be removed from the shelf. The library wasted precious dollars buying it. A note about its context wouldn’t have helped, but a forward about the book at the heart of the TIMES story is necessary:

“If you are taking a piece of iconic journalism and reissuing it, it is probably in the interest of the reader of today to place it into a context that makes sense,” said Peter Osnos, the founder and editor at large of PublicAffairs Books, which handles numerous works by journalists. “That doesn’t change the value of the literature.”

Context can be everything but sometimes even context isn’t enough.

I once taught Charlie and the Chocolate Factory in a BA creative writing class. Never again. Even with a lengthy discussion of racism not one Black student turned up the following week. When I discussed it with some it became clear that they were upset by even their more liberal peers’ comments (“you are over reacting” was typical).

I might teach it in a history class where students were more familiar with the theory arguments and the period. But I’d think hard.

SUCH an important and problematic topic. I wrote at great length about this over the summer, in response to an idiotic piece in the NYTimes (my post is at http://themovingcastle.blogspot.com/2012/06/how-not-to-read-racist-books-to-your.html). in that instance, I was thinking primarily of the white parent and child – a more localized, specific target, where I think it’s actually hugely important to see the appalling attitudes of the past. Erasing them lets white folks/dominant culture off the hook, in a way; it lets them forget about the deeply troubled past, a past which created the world in which we all still live. THIS post, and Debbie’s as-ever insightful response to it, makes me think about these books in the wider world. I do think making different choices in the classroom is probably the best solution, particularly with younger readers who might not yet be at an intellectual stage where critical thinking and questioning of a text’s ideologies are an obvious or ready response. I also think that training book-providers (teachers, librarians, pretty much anyone in a position to read aloud and enforce a text on kids) to respond to individual complaints and concerns better would go a long way toward making a difference. The only correct response when someone says “that book/word/joke/story is racist and makes me feel bad,” is to say “oh my gosh, I’m so sorry, I didn’t know/realize, let’s pick another book.” There are SO many good books out there that don’t have racist or sexist components that it simply doesn’t make sense to use any other books in a public setting.

I will add that I find it interesting that – as always – the discussions around erasing past textual instances of racism – are focused on children’s texts (and Huck Finn, which is NOT a children’s book, despite what anyone might say); there doesn’t seem to be much concern, beyond a very small, mostly academic cohort, about the deeply racist and maybe even more often monstrously misogynistic content of “adult” books of the past. Or the present, for that matter – sexist, racist books are cranked out and land in the bestsellers’ list all the time (Grisham’s *A Time to Kill;* Larsson’s *Girl with the Dragon Tattoo* trilogy, etc).

I’ve always felt ambiguous about this but to date have tended to come down on the “How do we expect that 9 year old child of a German mother and Sengalese father to contextualise a word that she knows only too well we can not imagine how it makes her feel” side of the fence. On the other hand, I also worry (like the previous commenter) about letting us privileged white folk off the hook. My 9yo is a big Beano fan and recently picked up an annual from 1986 which featured a jaw-droppingly racially stereotyped story. He’d never encountered anything like it and so had no context in which to find it other than funny (clearly it was an epic teaching moment for both of us). The problem is how to provide those teaching contexts without hurting others. Or patronising them.

Sorry, that isn’t terribly helpful.

I had a similar experience to Farah a couple weeks ago with Diana Wynne Jones’ Castle in the Air, the prequel to Howl’s Moving Castle. The freshman comp class I teach is also supposed to deal with issues of race, class & gender so I thought we could have a really interesting discussion & get some good writing on the text.

I am lucky enough to have two Muslim students, one of them actually from Saudi Arabia, in my class, which meant that pulling apart the stereotypes was pretty easy. Unfortunately, after that line in the sand was drawn, my students were so angry, they couldn’t make themselves engage critically with the text, the purpose of which isn’t to make fun of Arabian cultures but to point out the ways that non-white perceptions create a pseudo-Arabian culture, although the overwhelming consensus was that it’s not successful. They pretty much just stared at me for two class sessions and told me the satire failed. Race is such a hard thing to talk about anyway; they just shut down.

Bah… I can’t edit the comment. It should read: “the purpose of which isn’t to make fun of Arabian cultures but to point out the ways that perceptions of non-Arabic cultures (read: western culture, really) create a pseudo-Arabian culture, although the overwhelming consensus was that it’s not successful.”

Also, that should say sequel. I think I need a nap…

Pingback: HBook Podcast 1.11 – Bowdlerizing (or not?) — The Horn Book

Pingback: The book | Jennifer Macaire