This is the paper I gave at Diana Wynne Jone: A Conference, in at the University of the West of England, Bristol, July 2009. It’s a mix of personal anecdote and analysis of English fantasy and Australian children’s fiction of the 60s and 70s. But mostly it was, and is, my heartfelt thanks and tribute to Diana Wynne Jones and everything she and her books have meant to me.

_________________

From Alice to Aiken in the Antipodes:

An Australian Childhood spent in Fantasy England

or

How Diana Wynne Jones Changed My Life

I’d like to begin by explaining that this paper is not as perhaps as Diana Wynne Jones-focused as most of the papers you have heard this weekend, which I am sure is probably clear to you from the title and my abstract. It is, as you might have guessed, something of a perambulation through my childhood reading, which in fact did not include Diana’s books at all—nor Joan Aiken’s for that matter, as far as I can remember, although her name was certainly familiar to me and I have read and forgotten far more books as a child than my poor old 45 year old brain can recall. You’ll have to forgive me that small fib in my paper title—I liked the assonance too much. On hindsight, it could have been from Alice to Uttley, as Uttley’s A Traveller in Time, while not a fantasy of the sort I’ll be mostly addressing today, was one of the most important books of my childhood, and certainly gave me the same sort of transformative experience in the reading that I found in the books that are the focus of this paper.

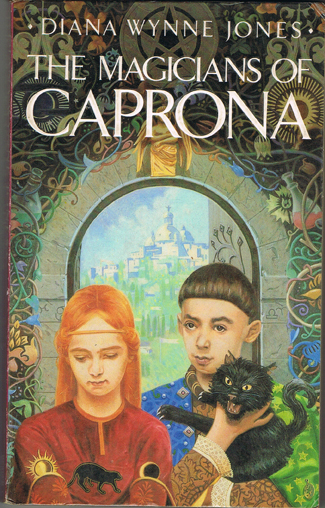

So why am I presenting a paper about my childhood reading at a conference dedicated to the work of Diana Wynne Jones when I did not in fact come across her work until I was in my late 20s? Having been born in 1964, I would have been quite young enough in the 1970s to have read and enjoyed her early works, which I can only presume were published in Australia more or less contemporaneously with her UK editions[1]—our bookshelves and libraries were full of English children’s books—but for some reason I did not come across her until the late 80s, when I was enrolled in a post graduate program in children’s literature with Professor John Stephens at Macquarie University. John set two of Diana’s books on the course—The Eight Days of Luke, which I found interesting but which made little impression on me—and The Magicians of Caprona, which, quite literally changed my life. How and why I will come to.

But first, let me tell you about my Australian childhood in the 1960s and 70s, which brings me to the second half of my paper’s title: An Australian Childhood spent in Fantasy England.

Although I read and enjoyed many Australian writers as a young child growing up in the Blue Mountains and in Sydney in the 1960s and 70s (and I will speak about some of those books and authors later), my childhood reading was dominated by English books and writers, and primarily English fantasy writers of various shades. In a way, my reading reflected the cultural caste of my childhood—a recognisably Australian child with typically Australian childhood experiences, I nevertheless think of my childhood as having a somewhat British cast—my family just four generations from England, our TV was dominated by English dramas and comedies, we still ate a full roast dinner with pudding for Christmas, no matter the heat, and we were all quite proud of the fact that our mum looked like the Queen. I know, superficial at best, but at that time Australia was still very much finding its own identity, culturally and politically, as distinct from Mother England, and while this period saw the beginning of the end of the cultural cringe in Australian arts and letters, we were still very much culturally influenced as a society by Britain. These days, of course, the US influence has a far greater hold, but that’s another paper for another conference.

So to get to the point, what does an Australian childhood spent in fantasy England look like?

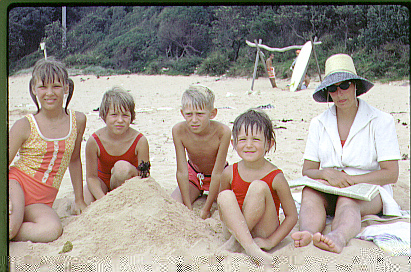

I imagine for many of you, this image represents exactly what you bring to mind if and when you think of an Australian childhood. Yes, that’s me, all salt-crusted and sandy-bottomed, with my two sisters, my brother and my mother at Macmasters Beach on the Central Coast of NSW in the summer of 1969-1970. Macmasters Beach was where we spent two weeks every summer—it was more or less our family home, as my father was a Methodist minister (yes, shades of yet another favourite English writer of my childhood, Noel Streatfeild), and we lived in church houses all our growing-up years. It was also the site of many hours, not just of sand and surf and sun, but of fantasy play—much of the same kind that Nick Tucker describes as characterising his and Diana’s childhood at Coniston Water[2]—on the white sands, on the craggy sandstone rock faces overhanging the beach, and in the bushy backyard of our little fibro holiday house.

We played those games at home too. In the 60s, home was Katoomba in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, a place still full of unspoiled native bush and rich in imaginative possibilities for childhood play. In the 70s, it was suburban Sydney, devoid of anything natural much, except for two marvellous trees worth climbing and reading in. But in both homes, Sydney and the bush, we made, even literally mapped fantasy lands in our back yard, and played out our favourite stories from books and TV. (At school, I remember endless hours replaying the night before’s episode of HR Pufnstuf, which may appear to have nothing to do with this paper, but if you know the story of a boy with a magic flute spirited away to a strange island full of fantasical creatures, you’ll understand it’s not far removed at all from the books I’ll be talking about today.)

Going back to Macmasters Beach and my somewhat grumpy looking family—we probably all had sand up our dacks, and Mum looks like Dad interrupted the crossword puzzle—despite being in that most iconic of Australian settings—the beach—every summer was partly spent, at least in my head, in England. I would re-read the copy of Enid Blyton’s The Castle of Adventure that stayed at the house at Macmasters, exploring the Castle in my imagination, when I wasn’t staring up at the immense gum-trees in our scrubby back yard, wondering what lands might be passing by as I watched.

It was in fact a very Blyton childhood—at least until that critical age of about 12 when I decided that everything those librarians said about her books was probably true, and I put away childish things. But before that day, it was The Magic Faraway Tree and The Wishing Chair all the way for me—stories of children into whose lives came that most remarkable of things—magic.

But it wasn’t just Enid Byton whose very English tales of adventure and magic coloured my childhood reading, and it wasn’t just in the summer that I dreamed of mysterious castles and magical chairs and lands of endless ice-cream and cake. There was Nesbit and Norton, the two Lewises—Carroll and CS—even the remarkable Ruth Manning Sanders who, while not strictly speaking a fantasy writer, was nevertheless a writer who could regularly be relied upon to completely transport me to another time and place, as much by her extraordinarily inventive use of language that created a sense of “other” like perhaps no other writer I have ever read, as by the fantastic characters and marvellous creatures that peopled her tales of the mysterious and arcane.

So what exactly was it about these books that so entranced me, and what was it in Diana Wynne Jones’s work that connected me so strongly back to my childhood reading when I read her nearly twenty years later?

In his paper “Pleasure and Genre: Speculations on the Characteristics of Children’s Fiction”, Perry Nodelman writes about the kinds of children’s books that bring him the greatest pleasure, and these are, as he describes it in a phrase that coalesces for me my own childhood reading preferences, books that “deny impossibility”. Lucy—with whom I fiercely identified as the youngest of four children—could walk into Narnia through the back of a wardrobe. There was a land at the bottom of a rabbit hole, small people could indeed live under the floorboards, and that chair, if I just looked at it sneakily sideways enough, surely had little wing-buds on its legs.

You may perhaps be wondering, what of the Australian fantasy of the time? Well, to put it simply, there wasn’t much. I have a few illustrations to show you that will demonstrate something of the early history of Australian children’s fantasy. Often, the work of the early 20th century Australian children’s book creators, like Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, drew very heavily on the English tradition of woodland creatures and delicate, English-looking fairies.

And when they tried to bring in an Australian element—as you’ll see in this next image—well, the results were a little ridiculous!

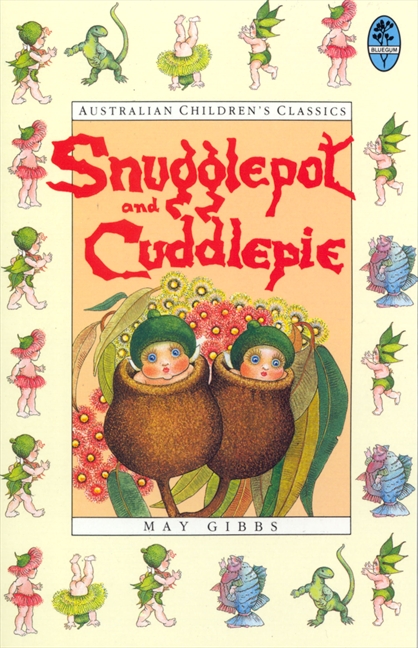

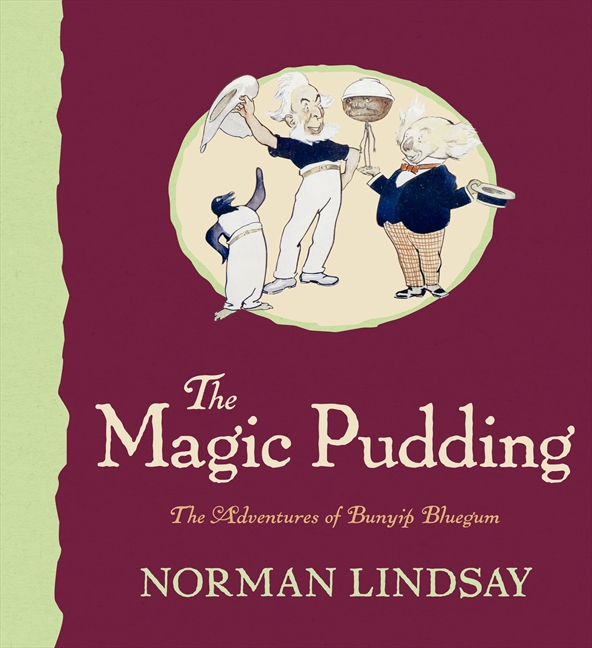

There were some successful attempts at a more purely Australian fantasy from writers and artists such as May Gibbs and Norman Lindsay, but they largely—and this is true of Gibbs in particular—drew on the natural world for their vision of a fantasy Australia. Now, I loved May Gibbs’s books, and Lindsay’s The Magic Pudding, but I certainly never felt as if I entered the story in quite the same way as I entered Narnia, partly because they simply weren’t “other” in the same way that fantasy England was, but also largely I think because these were stories totally devoid of human children. They were also, by the time I read them in my childhood, definitely showing signs of being from another era altogether.

I’m well aware, of course, that the English fantasies I am speaking about also represented an “older” version of England (albeit a fantasy one) than the actual England of the swinging sixties and sassy seventies. Karen Sands-O’Connor in her essay Nowhere to Go, No-one to Be identifies the reason this older, gentler, perhaps even more genteel England was so attractive to readers like myself: because it was a safe and welcoming place for children. If you’ve not read this paper, Sands-O’Connor takes as her examples Christopher’s shortlived visit to “our” world, 12B, in The Lives of Christopher Chant, and Janet’s decision not to return to her/our world in Charmed Life, but it’s an argument that applies beyond these characters. Sands-O’Connor observes “it is better to be in a potentially dangerous and magical secondary world than in a present, primary world where your own parents are absent (the Pevensie children) or uncaring (Janet)”.

[Just a footnote: I’m not sure you could argue the same for the Australia of Gibbs and Lindsay in quite the same way—Snugglepot and Cuddlepie is full of the dangers of the Australian bush, and the Australia of The Magic Pudding is full of conmen, thieves, liars and braggarts. They were fun places to visit, but I certainly didn’t want to live there.]

I think for me as a child NOT from England, my attraction to the old-fashioned fantasy version of England went beyond that safe place that Sands-O’Connor identified. For me, this was a place where magic happened—and it certainly wasn’t happening in the contemporary Australian books I was reading at the time.

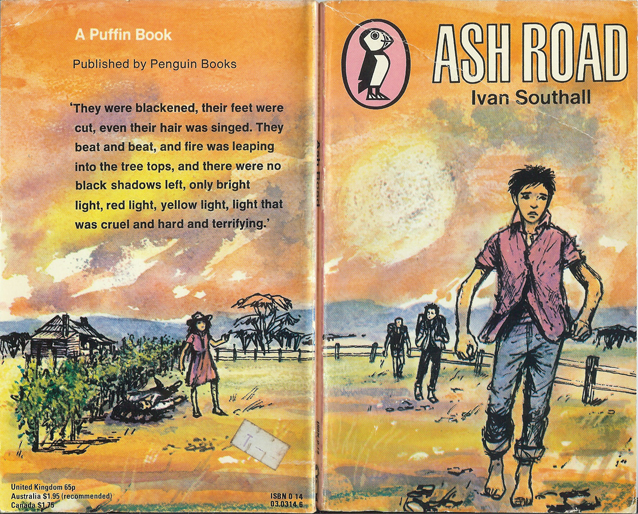

The Australian writers who were writing for children in the 60s and 70s, and that I was also reading during my childhood, had more or less abandoned any notion of an Australian fantasy, and was focusing almost exclusively on realistic fiction, much of it set against the dangerous Australian landscape and climate. Books like Ivan Southall’s Hill End, Ash Road and To the Wild Sky (his Earth, fire and air trilogy) and Lilith Norman’s Climb a Lonely Hill. Their covers give you some indication of the content:

In a sense, these books are the antithesis of Nodelman’s “denial of impossibility”. They were books that took realism to an extreme—the extreme of the Australian landscape and climate. They are books about children forced into a battle for survival against the elements; stories of car and plane crashes in the outback, bushfires and floods.

Maurice Saxby, who we affectionately refer to as the Godfather of Australian children’s literature, placed these books in their historical context in Images of Australia: A History of Australian Children’s Literature 1941-1970 (Scholastic 2002), writing the adventure of personal survival and victory over self-doubt had been gathering force in Australian writing for children… Citing Dr Belle Alderman, Saxby goes on to say writers such as … Ivan Southall use setting or landscape not only to map a territory but to affect profoundly their characters or to demonstrate how characters interact with their particular home in the world.

Now, strange as it may sound, stories of “this particular home in the world”—that was supposed to be my home—were in many ways as foreign to me as the enchanted woodlands and magical castles of the English fantasy I was reading at the same time. Of course, I was familiar with the Australian rural and bush landscape and with tales of survival in the Outback. You can’t grow up in Australia and not be influenced by the iconography of the landscape. But by the time I was seven and fully hitting my stride as a reader, we were living in a very working-class, suburban, highly multicultural section of Sydney, where the greatest danger to one’s survival was being knocked over by a car when one was walking home with one’s nose stuck in a book. I was in no danger of drought or flooding rains, nor of bushfire, and so in a sense these Australian books depicted as fantastic a place to me as Narnia or Arrietty’s home under the floorboards. And while I read them and enjoyed them, I didn’t love them as I loved your cosy English fantasyland.

(Just an aside: these books pre-date Patricia Wrighton’s attempts to marry Aboriginal spirituality and lore with the adventure novel by a handful of years. I’m not going to address those books here today: these books, while certainly historically an important endeavour to create a uniquely Australian fantasy narrative, they are now considered highly problematic in terms of their appropriation of Indigenous belief systems—and that’s a whole other topic for another day and a different conference.

In speaking of the books that “deny impossibility”, Nodelman makes specific reference to Charlotte’s Web, Beatrix Potter, Sendaks’ Wild Things. For me the denial of impossibility went beyond talking rabbits, word-weaving spiders and fairies at the bottom of the garden—although I did always keep a watchful eye out for Pookie the Flying Rabbit in amongst the thousands of deadly snakes and spiders that, as I’m sure you all know, populate every Australian backyard. (That’s a joke. Well, mostly.) The best kind of books for me as a child were those that promised me a journey from this world to another, and in this I have found a kindred spirit in Frances Spufford, who in his delightful and robust journey through his childhood reading said this of his favourite fantasy novels:

My favourite books were the ones that took books’ implicit status as other worlds, and acted on it literally, making the window of writing a window onto imaginary countries. I didn’t just want to see in books what I saw anyway in the world around me, even if it was perceived and understood and articulated from angles I could never have achieved; I wanted to see things I never saw in life. More than I wanted books to do anything else, I wanted them to take me away.

The Child that Books Built, Francis Spufford p.82

Spufford also writes about the kind of fantasy he and I both favour: the portal-quest fantasy:

And once opened, the door would never entirely shut behind you again. A tincture of this world’s reality would enter the other world, as the ordinary children in the story—my representatives, my ambassadors—wore their shorts and sweaters amid cloth of gold, and said Crumbs! and Come off it! among people speaking the high language of fantasy; while this world would be subtly altered too, changed in status by the knowledge that it had an outside.

p. 85

And if it could happen to those ordinary children—those representatives and ambassadors in the shape of Lucy and Alice and even Arrietty—and I’m even going to include Penelope Cameron Taberner (A Traveller in Time) in this—then it could almost certainly happen to me. These stories opened up and invited me into worlds where I could not only encounter magic, but perhaps possess it.

It was clearly the existence of magic and the possibility of entering the “other” that attracted me to these books, and I think I was quite conscious of that fact as a child. As an adult, I also see that there is something in the telling of these tales that encouraged this deep engagement with the fantasy world. It’s what Barbara Wall in The Narrator’s Voice: The Dilemma of Children’s Fiction calls the “twentieth century” narrative voice, and largely credits its invention to Edith Nesbit, whose narrative personality she describes as expansive and outgoing, as well as “cheerful, irreverent, bubbly”. This narrative personality, as Wall calls it, places a strong emphasis on the partnership between narrator and narratee—that “at her best and most characteristic Nesbit managed to suggest a relationship in which narrator and narratee are partners, sharing the fun of the story”.

let me give a few examples to illustrate the kind of narrative voice I am speaking about. I’ll start with Mrs Nesbit, as Wall has taken her as the inventor of this voice. This is from the first chapter of Five Children and It: she’s speaking about London and why it’s so bad for children:

And nearly everything in London is the wrong sort of shape—all straight lines and flat streets, instead of being all sorts of odd shapes, like things are in the country. Trees are all different, as you know, and I am sure some tiresome person must have told you that there are no two blades of grass exactly alike. But in streets, where the blades of grass don’t grow, everything is like everything else. This is why many children who live in towns are so extremely naughty. They do not know what is the matter with them, and no more do their fathers and mothers, aunts, uncles, cousins, tutors, governesses, and nurses; but I know. And so do you, now.

Here’s another passage, also from the start of Five Children that even more clearly demonstrates the narrative personality Wall writes about:

Now that I have begun to tell you about the place, I feel that I could go on and make this into a most interesting story about all the ordinary things that the children did—just the kinds of things you do yourself, you know—and you would believe every word of it; and when I told you about the children being tiresome, as you are sometimes, your aunts would perhaps write in the margin of the story with a pencil, “How true!” or “How like life!” and you would see it and very likely be annoyed. So I will only tell you the really astonishing things that happened, and you may leave the book about quite safely, for no aunts and uncles either are likely to write “How true” on the edge of the story. Grown-up people find it very difficult to believe really wonderful things, unless they have what they call proof. But children will believe almost anything, and grown-ups know this.

Here. also a childhood favourite, the opening paragraph of Mary Norton’s Bedknob and Broomstick:

Once upon a time there were three children and their names were Carey, Charles and Paul. Carey was about your age, Charles a little younger, and Paul was only six.

And I’m sure we can all bring to mind a similar narrative voice from Lewis in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: that bit about Lucy being a sensible girl and not closing the wardrobe door behind her is a direct address to the reader.

Of course, Nesbit didn’t invent the direct address of the narrator to narratee—you find it a little in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and in other 19th century children’s books—including my favourite Australian children’s book from my childhood, Seven Little Australians (still no fantasy!). But Nesbit did perhaps make that voice more inviting, by, as Wall puts it, making the narratee a partner in the storytelling.

Nesbit, of course, is the writer Jones is most commonly compared to, and it was this narrative voice that I instantly recognised when I first read The Magicians of Caprona. Here I was back in the hands of the same storytelling tradition that had spoken to me so deeply—and indeed, so directly—as a child.

What I think appeals to me the most about this narrative voice is that it assumes that the reader is part of the world of the story. You are the same age as Carey… You know that trees are different… you know never to close a cupboard door behind you… you belong in this world where magic exists and astonishing things happen to ordinary children. For me, though, Jones took it to another, entirely more satisfactory level than Nesbit and her forebears and imitators.

I’m sure you all know the glorious, enchanting beginning of The Magicians of Caprona. I suspect it’s my favourite opening passage of any book ever, with Charmed Life coming a close second. I’m beginning three paragraphs in after the preliminary paragraphss about Spells being the hardest thing in the world to get right, and Angelica turning her father green…

The best spells still come from Caprona, in spite of the recent troubles, from the Casa Montana or the Casa Petrocchi. If you are using words that really work, to improve reception on your radio or to grow tomatoes, then the chances are that someone in your family has been on a holiday to Caprona and brought the spell back. … You can get spells there from every spell-house in Italy… If you want to find out who made your spell, look among your family papers…

Where I think Jones differs from Nesbit—where I think she’s more subtle in the use of this inviting narrative voice, and why I think it is so much more successful for the contemporary reader—is in the way Jones’s implied narrator assumes the implied narratee is part of the world of the story being told. Nesbit, it seems to me, has to work a bit to cajole the implied narratee into the world of the story. Despite what Wall says about the implied naratee being a partner in Nesbit’s storytelling you always know you are being told a story; as per those “Now as I have begun to tell you”-style narrative observations.

Jones just assumes you’re there. You’ve been to Caprona, you have the spell scrips, you are part of this world. Much as I enjoy the bubbly Mrs Nesbit, I prefer the matter-of-fact Ms Jones. Quoting Perry Nodelman again; “I love [the impossible] best when it happens in the context of a firmly established possible, and when the narrative in which it occurs takes a decidedly matter-of-fact attitude towards it.” It’s this matter-of-fact acceptance of the impossible that allows the reader to step whole-heartedly into the world of the book as if they always belonged there.

And for me, as a third person narration, this voice, or rather the effect it has on the implied reader, stands in contrast to the accepted wisdom about what is the proper engaging narrative voice for children’s fiction. The assumption tends to go that it’s got to be either first person or a closely focalised third person. Andrea Schenke Wyile proposes this is her paper “The value of singularity in First- and Restricted Third-Person Engaging Narration”, arguing that “The narrator seeks to reconstruct the events being related in a way that engages readers, in a way that invites them to consider themselves in, or close to, the position of the protagonist.” There’s an implication—and I think it’s a commonly held belief about narrative voices—that the third person omniscient doesn’t want to, or even can’t achieve this. I think this can be true. It was certainly true of the third person omniscient narrators of those books of fire and flood and disaster in the outback that I spoke of earlier—this example from Ivan Southall’s Ash Road demonstrates the point. This voice was deliberately, I would argue, creating a distance between the implied narrator, the action, and the implied narratee:

On Friday, 12th January, in the late afternoon, the three boys camped in the scrub about a mile from Tinley. It wasn’t the best spot to pick, but at least there was water; and they were very tired.

They had escaped from the city for a glorious week of freedom in the bush. They had never done it before. They had planned it for months. At first their parents had said no, firmly no, but the boys had nagged and nagged. At last they hit upon the ruse of encouraging the idea that Harry’s parents would agree if Graham’ parents would agree if Wallace’s parents would agree. In the long run the ruse had worked. The different parents—who rarely saw one another—were not anxious to be regarded by the others as over-protective. After all, the boys were all soon to be fourth-formers—old enough, surely, to take care of themselves and to keep out of trouble for a few days. Not so many years back boys of that age had been out in the world earning a living.

Ash Road by Ivan Southall (1965)

By contrast, Jones’s narrative voice in Magicians and other books—third person, omniscient—had the opposite effect. It does for the reader—this reader, at least—what Shwenke Wyile argues is achieved only by the First- and Third-person narrative voice. I just think this is completely masterful.

And when you combine this utterly masterful narrative voice with the over-arching theme of her books that so many people have identified this weekend—that of the apparently ordinary child being found to have remarkable and hitherto-unrecognised gifts—it’s a wonder to me Jones isn’t more widely known and loved than she is. It’s what Farah Mendlesohn calls the “Künstlerroman”—the growth of the child into the artist—and Charles Butler describes as “the realisation of personal potential”, but oh, what potential! This isn’t just being good at the piano, or hitting home runs, or clever at maths. This is the possibility of being extraordinary—and what child doesn’t secretly wish, or perhaps even believe, this for themselves.

Now I am quite aware that Jones does not always use this particular narrative voice of direct address to the reader, just as I am aware that Blyton never used it (see the footnote as to why Blyton worked for me as the exception to this “rule”[3]). You find it explicitly in the opening paragraph of Howl’s Moving Castle, and I would argue that it’s there implicitly, without the use of the personal pronoun/second person address, in all four of the original Chrestomanci novels—still my favourite of Diana’s books for deeply personal reasons. Because as I said, it was The Magicians of Caprona, and subsequently my discovery of the Chrestomanci sequence, that changed my life.

And so at last I come to it—how Diana Wynne Jones changed my life.

I’m sure it will come as no surprise to you to hear that I was a child for whom books were essential. I could read before I started school—I don’t remember not being able to read—and when the time came to choose a university course, the only thing I wanted to do was to study English. And the only thing I knew to do with an English degree was to become a teacher. And so I did.

I taught for five years in public high schools in the south-western suburbs of Sydney, partly by necessity—that’s where the jobs were—but also partly by choice. My lecturers at Macquarie University in the 1980s instilled a strong sense of social justice and responsibility in me as an undergraduate and I wanted to work in schools where I thought I might make a difference. And I loved those school and the kids I taught, but being an English teacher wasn’t exactly what it looked like in all those movies (thanks for that, Robin Williams…). There was so much I loved about teaching (mostly the kids) but often literature was a long way down the list of what I had to deal with on an average day in the classroom. And anyone who remembers the political climate around NSW public education in the late 1980s will recall it was a tough time to be an idealistic young teacher.

And like many of us for whom the great love of our life—books and reading—becomes the everyday chore of our working day, I wasn’t often taken away by books any more. And I missed that.

So I went back to my university, looking for some intellectual stimulation and renewed motivation and met Professor John Stephens, who suggested I enrol in his post-graduate course in children’s literature. I didn’t take much convincing. I’d never stopped reading my favourite children’s books, and I tried to keep up with contemporary children’s and young adult literature for my teaching. The chance to thoroughly absorb myself in children’s literature at post-graduate level just seemed like it was too good to be true.

And it was in that course that, as you now know, I was first introduced to the books of Diana Wynne Jones.

The first, as I said, was The Eight Days of Luke. I liked it well enough—familiar territory, the English fantasy novel, and I was a bit thrilled with the Norse mythology twist, but while it appealed intellectually, it didn’t quite capture me emotionally. I didn’t want to be there with David and Luke—it didn’t take me away.

But then came The Magicians of Caprona, and after it, the rest of the Chrestomanci books (the original four titles), and then Dalemark and Howl and Polly and Hexwood and on and on. I’ve not read everything Diana wrote, and I’m certainly not as assiduous a fan as many people here today—but ask me my favourite writer, ask me my favourite book and despite all the many writers and books I have loved, if there has to be just one, it will always be Diana and it will always be Magicians, because of everything she, and it, have come to represent for me.

I know I am preaching to the converted here, so I know that you will understand that it is not hyperbole when I say that this book changed my life. It did so by reminding me of the deep place books held in my heart, mind and imagination as a child, and of the transformative possibilities of “the right book at the right time” (or, as the book says, “the right words delivered in the right way”), and of why I loved to read in the first place. And it made me change the entire direction of my career, and thereby, my life.

And it did so, it could do so, because it is a book that celebrates the power of story and of language, and in a very real sense it cast a spell over me, making me feel like I was 12 years old again, with that pre-adolescent capacity to totally give oneself over to the power of words and of story. And remembering that feeling made me want to do something that might make the experience available to other children. This was what I wanted to do, something I didn’t seem to be able to do in the way I had always thought I would in the classroom. Somehow, I wanted to do work that somewhere along the line opened up the possibility for other kids to experience what the love of books and reading had given me. To be transformed. To be taken away. (And yes, the irony is not lost on me that I felt I had to take myself away from the classroom in order to achieve that.)

And so that’s where I am now. Have been, for 20 years. Gave up that, in retrospect, secure and pretty well-paid teaching job and struck out without anything even closely resembling a Tough Guide, on a career that has now encompassed editing books and magazines for children, writing about books and authors and about books for children and teenagers, teaching about children’s literature. Getting closer to the actual demographic, I’ve organised more events and programs and workshops and the like with authors and for young people than you can shake a wand at. My work has taken me all over the world and has allowed me the friendship and collegiality of some of the greatest people I could have ever have imagined even meeting—many of them writers and illustrators, many of them academics and teachers and librarians, some of them booksellers and many of them simply fellow lovers of story.

And it’s all brought me round to my current work, running a project in western Sydney, working with schools and public libraries, arts and community organisations, developing literature-based programs to encourage kids to enjoy reading, to nurture young writers and to increase awareness of the importance of books in the lives of young people.

This project has such potential to make the kind of difference in the lives of young people that I wanted to make all those years ago when I was a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed young teaching graduate. I can’t think of a better job, a better place for me to be.

So this paper, as wide-ranging and perhaps sketchy in parts as it is, is my personal thanks and tribute to Diana Wynne Jones. I might have ended up here, or somewhere like it, in any case, but the fact is I have always, will always, know that she is a huge part oh why I work with children and their books, why I strive to help them find ways to deny impossibility and to believe that they too can be remarkable. I feel so privileged to work in this field and I owe so much of it to this one extraordinary writer.

But wise and wonderful as Diana is, she was wrong about one thing. The best spells don’t come from the house of Montana or Petrocchi. They come from the house—the many houses—of Diana Wynne Jones.

[1] Apparently Diana’s books were not published or distributed in Australia until the 1980s, so I missed them in my late childhood/early adolescence for good reason.

[2] From Nicholas Tucker’s keynote on the first evening of the conference.

[3] Of course, where my thesis about the attraction of this engaging, encompassing, inviting narrative voice ends is with Blyton. If she ever used this Nesbitesque voice, I could find no trace of it in my wanderings back through her books for the purposes of this paper. Instead, I found the “powerful omniscient narrator” that Peter Hunt so roundly criticised in Criticism, Theory and Children’s Literature as being “so obviously present and dominant and more knowledgeable than the implied audience, that the interaction cannot seem to be between peers” (106). Indeed, Blyton frequently addresses herself as narrator, with all those “my goodness”es and “dear me”s, but rarely if ever does she openly invite the child narratee into the world of the book. Surprisingly, given my preference for that kindly, take-you-by-the-hand as they bring you over the doorstep narrator, I obviously wasn’t alienated by Byton’s controlling narrative personality. Perhaps the power of her imagination overcame the bossiness of her tone.

___________________________________

I was honoured that this paper was mentioned in The Guardian book blog report on the conference.

Pingback: In a related world… | Misrule

Pingback: 2012 AWW Challenge: Children’s Fiction « Australian Women Writers Challenge