Sydney, October 2003

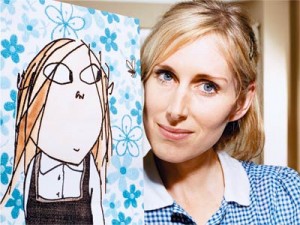

Lauren Child was in Australia for a publicity tour and the bi-annual Children’s Book Council of Australia conference. I interviewed her in her hotel room overlooking Sydney’s Botanical Gardens. The interview was published in Good Reading Magazine in January 2004. This is the full transcript of our conversation.

_________________________

I first came across Clarice Bean in a bookshop I was working in at the time, and I hadn’t heard of you, hadn’t heard any pre-publicity, and so I came to Clarice Bean completely fresh, and I can remember standing in the bookshop, just laughing out loud and being utterly charmed and delighted by this really fresh approach to a picture book. I’ve been reading your history with art school and design work and so on with interest. I was interested that at art school they didn’t teach you the fundamentals of book design, like gutters and that kind of thing, because what strikes me about — you know how people say about writing and so on you need to know the rules to break the rules? There’s something really fresh about your books — you seem to really understand how a book works, because you’ve taken it apart and put it back together again… Starting the story before the imprint page, playing with design and so on. I’m interested in how you came to that approach.

Part of it maybe is not knowing all the rules.

Not being bound?

Yes. I wasn’t taught any of that stuff, which I do think you should be taught. Generally it would be helpful.

Well, it is teachable, as you’ve said.

Yes. But perhaps not knowing it means you fumble your way through it and you get something different. I think maybe also I wrote, I’d tried writing before and publishers were always saying “write a little bit more like this or a little bit more like that”…

More conventionally? More plot based?

It was ages ago when I was trying to write the story, and they have a very… I can see why it happens, they don’t really want to take a big risk on somebody new, and nobody wants to publish something that won’t sell, so it makes sense that they want you to write a little bit like somebody else before, but I found it very difficult, because I was always trying to write something that would fit in with what they wanted. In the end I wrote Clarice Bean, which was a long time after I had written things in my early twenties, and nothing got through and I’d given up on the idea. And then really because I wanted to maybe come up with a character that could be used in animation or product design…

So you had that idea quite early on.

Yes, I’d given up on the idea of being an illustrator or a writer. It was really a means to an end, to get into something else, so perhaps that made me approach the whole writing thing in a different way, I wasn’t all that interested in that side of it. I just started writing about a character, rather than trying to make a very plot-based story book.

And was there some resistance from publishers to that?

Well, I just kind of wrote and wrote, and then I knew very much how I wanted the book to look, so I set it all up, I did some sample spreads, and I went and worked with a graphic designer friend of mine, and we made all the type move in the way I wanted it too, and came up with the different fonts for each character.

I wanted to ask you about the fonts…

So that was right at the beginning, I decided all those things. So then I put the two things together, so I’ve got the picture and I’ve done overlays of the text, so you could see how it would integrate with the pictures.

There’s a couple of questions I wanted to ask you about that. First of all I was going to make the comment that the convention about children’s books is that they’re really strong on plot, that children’s books are the last bastion of plot. You’ve proved that that doesn’t always have to be the case, although as for instance the Clarice Bean books have gone on the plot has become more fore-grounded, and then you’ve gone to the novel, which is something we’ll get back to. So that interests me. But also, in terms of the overall conception of the book — when I first read your books, it took me quite a while to realise — I’m not a visual person — but it took me a really long time to notice the detail of your books. I didn’t realise at first that they were collage, I didn’t sort of consciously notice, even though I know that Marcie’s got all the photos of boys in her room and so on, but it took me a while to actually see the different layers that you’ve built up there with text and drawings and photographs and then the fonts. There’s a real coherence to the books. It reminds me of, when I was at uni I was in a drama group, and there was a fellow I’d been to high school with who turned up at a performance and he’d become a makeup artist, a theatrical artist, and he said to me, “If people say to me after a performance, the makeup was great, I know I’ve failed, because they shouldn’t notice it.” I feel that way a little bit about your books, like I didn’t notice at first all the different— because they work together so well. So I’m just wondering how you conceive of all of those disparate elements. Do they sort of naturally fall together, or do you work with one element at a time, like text and then…

Yes, I think they just come, I think it’s a — while I’m writing, I’ll get a visual thing in my head of how the illustration should look like. Marcie’s room was one of those ones where I had very strong feelings that I wanted it to look a bit like a teenage magazine. So you’ve got that feeling that, yeah, you’re in her room and you kind of know what her room looks like, but some of it you know isn’t really there. It’s quite abstract in a way because it’s laid out like a magazine, and I left that picture right to the end that I had such a sure feeling of how I wanted it to be I kind of felt like I couldn’t do it. And it was one of those ones where I dreaded it because I thought, oh it’s just not going to come out, and it was one of those that just did come out exactly, it wasn’t this awful thing trying to get down on paper what I wanted. That’s the funny thing about illustration. Sometimes it really happens exactly how you want it to, sometimes it doesn’t, you can’t get it across and I would change things, and you keep changing them…

So do you start with a pretty fixed picture in your head of how it should look?

No, it’s usually quite a blurry vision! And you think, yeah, I sort of know how I want that to look. You have something in your mind’s eye, and you kind of think, it’s going to work, and then sometimes just getting it down on paper is just impossible. Or sometimes you do exactly what you thought was going to work, and it doesn’t, it just doesn’t quite look the same, and you’ll redo it and redo it. The last spread of That Pesky Rat, it was exactly that, where I had this kind of vision of how I wanted the old man and the rat to be sitting in front of the fire in a sort of quite gothic way, I suppose, having a little cup of tea together. And it suddenly didn’t make any sense to do that, because I looked back at all the other images, and the writing, and it suddenly all became about looking into windows, that this is about a character who’s spent his whole life yearning to have a home, and he’s always looking in, and he finally wants to look out, so I changed it, because I felt he had to be sitting in a window of his own with this man, his new owner. And that’s where you were going to get the cosy feeling from, that he’s finally made it. So things like that happen all the time. I would say sometimes I’ve got a very clear idea of what I want, but you don’t always get that in the end. I mean, illustration is such an odd thing, and I usually dread starting because there’s so much disappointment involved, because you’re trying to get something that you can’t always get. And at other times its such a surprise and it just happens.

I think sometimes, too, people underestimate — if you’ve got a more cartoony style, for want of a better word, it looks so spontaneous and fresh and quick and easy, but that’s not the case at all, is it?

No, it’s not. I think people —

If you’re doing it well it looks fresh and spontaneous and easy!

Yeah, you definitely want it to look like that. But I think people find it very hard to understand visual things in a way, because— I was debating with my…

Your minder?

My minder, who is the head of Orchard, and we were just talking about that whole thing, and I was saying how I definitely feel illustration is not considered as important as writing.

I think you’re right.

I definitely think that. She doesn’t feel that, because Orchard is the only publishing house that I’ve worked for that treats the designer as the editor. I think they’re really good at getting that right.

I wanted to ask you about the design of the books. The Clarice Bean books — Anna Louise Billson is credited as the designer on the imprint page, but the other books don’t have anybody credited. I was wondering about your relationship with the designer. I’m sure it varies from book to book and publisher to publisher… You did refer to that earlier, when you were starting out with the first book, you worked with a graphic designer friend. Do you consider the designer an editor in a way, like an editor who edits your text?

I think it’s a very similar job. What I would do with my roughs, and certainly with that first Clarice Bean, because— it wasn’t exactly my first book, but it was the first book I wrote… things like… if you saw the original for something like that… (indicates a spread) it would be pretty similar. This (Clarice twirling in the garden) is different because (the designer) had to reorder that because I had that (the text) moving around much more. I think that she felt we shouldn’t do that. But things like this one, this looks almost just the same. Basically with this one (Clarice twirling), things got toned down more, because I’d done things like when she’s says about twirling, and I’d done this so it was twirling, but it wasn’t logical enough, and things like this, I wanted to have the argument in between them…

Oh yes! Divide them.

It would make more sense, but because of the gutter it was just getting tricky, and that’s why we didn’t do it in the end. Here I’d had all the words falling out of his pockets…

It’s got a similar effect.

It’s just that sort of thing of — I think, it was one of the first books that I worked on, things like that had stayed and things like the writing being scrunched up, but it was sort of a lesson for me in toning down.

OK! But on the other hand you’ve said you’re going to be doing some new books with Penguin and you want to try new things there.

Yeah, in different ways. I guess when I’m doing a rough of something like this then I will usually do that on the computer, so I can see what it looks like, because now I’ve got to know my designers so well —

And they you…

Yeah, I can send them a much rougher thing, but with a book like this, I was working with a different designer on this, it was great, but I’ll generally do it as a visual note to myself rather than to her, so I did spend quite a long time…

And do you do that on the computer…

Something like that I did do, because I needed to know if it was going to work, whereas when I was first doing these books, I needed to know that she understood what I meant, and then once you’ve dome a couple of books you have a kind of shorthand between you, so it’s not a problem.

How many of the fonts have you created specifically for the books?

No, we’ve just used— I’d love to do our own fonts, but we haven’t.

The one that made me wonder was in Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Book, I think it’s when Herb’s in Little Bear’s bed, he’s in a bed anyway, it’s a quilted bed, and the letters have stitches…

Oh! That’s true! I think that my designer, David, did that.

OK!

I think he did. He adapted one…

That one made me think, I wonder if they invented that one.

I think he did in fact.

So it’s a very close relationship, working with the designer, then?

Yeah, it’s always really close. With that book particularly, we both spent hours doing that, where I didn’t just pencil in how I wanted it, I literally did put it in. It would have been the correct font, but that one, particularly that spread, because there’s so much text… I can’t actually do the illustration until I know that the text is going to fit in, because — I don’t have a copy of it (Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Book) — That was a really hard book, because I wanted you to feel like you were right in there, so it’s meant to look like, obviously it’s meant to look like you’re in the page, and so you can’t have it all abstract like this, because he’s actually going into the room, and everything, and it’s a very traditional fairy tale book. So therefore everywhere is wood panelling or carpets or quilts or whatever, so I did have to go through everything making sure I’d left enough space for all the text, which is why a lot of that I did do just by laboriously glueing it all in and then sending it to him, and then he would have to rework everything.

There’s a bit of a tradition of the fractured fairy tale. Did you feel daunted about trying to do something fresh with that? Because I think you have…

I didn’t really. I had this idea in my head — it was really all to do with this little boy who’d read my book I Want a Pet. He was really small, and his mother had relayed this thing that he’d said after they’d finished reading the book, he said “Will you take the book out of my room” and she said “Why?” “Because there’s a lion in the book.” And that had given me the idea of the story before. It’s a really simple idea but I hadn’t thought about it. And so I came up with that and wrote that. I was going to write it just as any old story, I was going to make something up, and I just thought, Oh, if you make something up, about an ogre or whatever, then the kid hasn’t got any — you’re having to explain the story, which hasn’t got a reference about the story that you’ve got with an ogre in it, and that it’s much easier to come up with something like little red riding hood, because they already know about the wolf and what the wolf does, and you don’t have to explain. And so that’s why I used the fairy tale. It wasn’t really intentional.

I think that’s a really common experience. As a teenager, I went through a period of reading horror and ghost stories, and I buried the books, so I wouldn’t wake up in the night and see the cover and give myself a fright, so even older kids have that experience. That’s interesting, because that’s two kids now that have sparked off a book; there was the little girl in Denmark who inspired Lola, who’s fabulous… What interests me about Charlie and Lola is that the books are about Lola, but Charlie tells the story. I wondered how you came to that decision, to have Charlie be the narrator.

I don’t know how it happened. I wanted to do something where it was just children’s voices. I had this really strong feeling about siblings and how they relate to each other, because I think as a child you do spend an awful lot of time with people your own age. I had two sisters and a lot of our time was spent squabbling or paying or whatever, and so I thought it would be nice to do a book where actually that’s all you see. You don’t see the parents. They’re referred to but you don’t see them.

I was interested that early on in your career you were directed to write about animals because kids like animals. But there seems to me to be a great strength in your books about families, about those familial relationships with Charlie and Lola and of course Clarice’s family. It strikes me that families are quite a strong point in your books, about those dynamics and so on. Even That Pesky Rat is about finding a family.

Yeah, it is. I’ve always been much more interested in the ordinary things that happen in your life that are funny, and I was always more interested in the forms of TV series where you had something extraordinary happening in the ordinary ? of your life. A film like Freaky Friday I loved, because — a domestic somehow — and so things which are about magic where it doesn’t really relate to my home life never really appealed to me quite so much. So watching something like “I Dream of Jeannie”, where you can imagine, oh, how would it be if you actually did have your own little genie… and how it relates to you…

So fantasies that existed within the real world would have appealed rather than, say, Narnia.

Yes, it does really, although I loved those books, but I liked them more when they… I guess I liked the first one the most because they were surprised by it. I love Woody Allen, because he’s always talking about very, very usual things in life, they don’t go off into mad fantasy, they tend to be more about conversation. And in some ways nothing really happens.

Well, conversation, that goes on to voice. The voice of… well, again, it’s interesting, because Lola’s kind of channelled through Charlie, although Charlie’s a good character in his own right, a lovely character in his own right, he’s so kind of, I don’t know, stoic almost!

Right.

But Lola and Clarice both have really particular voices. I particularly notice with Clarice, and I think you’ve developed it in the novel, because obviously you’ve got room to, there’s a kind of a wonderful blend of how kids really talk, like she says something about her “best thing”, and I was showing you the magazine where I work. We get letters from the kids, and they talk about their “best story” or their “best..”, you know, rather than their “favourite”, so I thought that was a really well observed — children’s usage of language. There’s also her, kind of, appropriation of language, that she’s heard adults say which she doesn’t always quite get on the mark, it’s almost the right context to use it, and then there’s her own language… Are you a listener? Do you people watch?

Yeah, I do, I do. I mean, I think adults say as many funny things like that as children. You hear it a lot. My sister does a bit, in fact, where she’ll get the words wrong, and I’m sure I do it all the time. And if you listen to people, their voice pattern, the way they construct their sentences can be very charming. I heard a friend of mine, it was just a slip, he’s a really great guy, and he’d been very ill, and someone said to him, how are you now? And he said, well, it’s all worth it for that, the adolescence makes it all worth it. I just loved it, he didn’t notice he’d said it. You get this kind of really brilliant thing where people put things together in such a funny way.

It’s like a fraction off, and yet it works.

Yes, it’s very funny. I remember I phoned my aunt. She was staying with her nieces, little girls, and I phoned her and I said, Oh, I’m just ringing up to say hello, how are you, and she said, Oh, well! A bit tired. We were up looking for spiders at two o’clock this morning. She meant that the children had obviously woken up in the night and there was a spider, and she had to get up, but it sounded like they’d all been up just looking for spiders as if it were a perfectly normal thing to do.

Clarice does that all the time, she repeats things her father says in the business context, but out of that context, and so — they’re almost clichés that people rattle off without thinking, but when you put them in her mouth they become — well, funny, but also quite pointed sometimes. Did it come quite easily, her voice?

Yes, I just kind of wrote, and I didn’t really know what age she was when I was writing, but I’d drawn a few sketches of her, but I just kind of wrote and wrote and wrote and little bits about each family member. So this is pretty much how it was. I edited out I think two pages on her father and one ended up being in What Planet Are You From… because I wanted to put in that whole bit about him cooking, but it wasn’t really appropriate for this book. And I’d written something about her mother and what she used to before she became a mother, and I’ve never used that. I might do. I really want to. Most of it, it was just pages, like this, and I gave it to an editor, I’d taken it round to several people and they all for one reason or another didn’t feel they could publish it. Then I gave it to one editor and she really wanted to do it and what she did was, she just switched round the passages of text. Because they were all written on separate pieces of paper, so “I want to put this here, this here and this here. What you’ve got is a kind of quest for peace and quiet.” So it’s less just like, you know, anecdotes, it actually makes sense of something. And then I just had to write the ending for it, which is when I came up with some of —this — had been written, but it wasn’t at an ending, and she suggested I write a bit more about that and make that the ending. And then in the end she couldn’t publish it, but it really helped. It showed me how you can actually use what you’ve done and regroup it.

Well, that extra eye looking at it…

Yes. It’s really interesting. I was always a bit daunted because I suppose plot’s not really my thing, probably because I’m not all that interested in it, but you do need something.

You’ve written a novel which does have much more in the way of a plot, with the mystery of Betty Moody’s disappearance, and the book project and K? and is he going to come through with the goods and so on, and Mrs Wilberton! I mean, I’m an ex-teacher and I sometimes feel a bit, you know, defensive on teacher’s parts, but she’s such a wonderful creation. You know, it reminds me a little bit, and I think there’s a bit of a — I don’t know, it’s like I was saying about all the Lemony Snicket type books… I don’t know if you know Angela Anaconda? The teacher in that reminds me a bit of Mrs Wilberton.

I was actually quite worried about that, because I’d written Mrs Wilberton, and then I’d had all that, and I thought, oh no!

But those things happen all the time…

You have to have your kind of ogre person, and — both my parents are teachers, so I didn’t feel that bad about doing it.

She’s not despicable.

No.

She’s not completely unjust and vicious and malicious, she’s just fed up!

She’s fed up, but she’s also uninspired. I actually got the idea for her — I was watching a documentary which was following a class of seven years olds, that transition from the infants into the juniors, and the children actually get— I can’t really remember that feeling of how scary that is, when you’re going up a level, and they feel terribly grown up suddenly, and they don’t feel they can cope with the work, and they kept talking about it all the time, it’s too hard, and you’re thinking, oh, you don’t know you’re born! But of course when you’re that age, it’s really daunting how much you’ve got to learn, and it all feels terribly important. Anyway, there was a woman in it who was rather like Mrs Wilberton, who was a real, kind of —

Been there too long…

Yes, all the time she was droning on at them. There was this real chatterbox called Roland in the classroom, all the time he got it in the arm. The whole thing of her just going on and on. I played it to my mum, and I said what do you think about her, and she said well, she’s an old bully, isn’t she, because that’s really what she was doing, she’d lost the whole thing. You don’t need to treat children like that to get them to do things. And so I thought it’s fine to have Mrs Wilberton in so long as I have Mr Pickering as being rather nice.

Yes, and Clarice isn’t completely virtuous in all of this.

No she’s not!

She falls off her chair on purpose…!

Yeah, I know! I want to show, I wanted them all to be rather rounded characters. So in the next novel I’m introducing one of the teachers that you think is marvellous.

So there is another Clarice Bean novel?

Yes.

More picture books?

Yes, we’re just sort of discussing that, because I was going to write another picture book, while I was in New York, which would be set in New York, and then I got really into doing the novel. But I would like to write a series of Clarice picture books which are set abroad, you’ve got that kind of feeling of coming back a little bit more to the feeling of the first one, where maybe there are less plot points, but we were just talking last night about doing one in Australia, because actually Australia is a fascinating country…

You’ve been here before.

Yes, I’ve been here before, but it’s sort of when — I don’t know if this is a British thing or a European thing, or what, but the distance, when we were little, thinking of Australia, it’s one of those places that seems so unimaginable, would you ever go there? And you’ve got wombats and possums and kangaroos and things that we just don’t have, and so it’s fairly amazing on that level.

The books have a slightly international flavour anyway. I wasn’t sure when I first read it whether you were English or not. The imprint didn’t necessarily mean that you were, it might just have been an English edition, and then when I read “My Uncle is a Hunkle” I got completely thrown, “Is she American? I thought she was English…” so there is a bit of an international flavour anyway. I was thinking as you were talking earlier when you were talking about voice… I interviewed David Almond earlier this year, and I’d read his books, and my brother-in-law comes from Newcastle as well, but when David read his books in his northern accent, it had a whole different feel to them. That interested me, to have read them and had one relationship with them, and then to hear them in his regional accent and to get a whole other feel to the characters and the setting and the book. It’s just an observation. Do you see Clarice as being from a particular place? Or any of the characters, in fact?

In a way I do. When I started writing I wasn’t quite sure where she would come from, and my first instinct was to have her come from Shropshire, which is where I come from, but it didn’t seem to fit with everything that she did, and I was living in London, in north London, in a fairly scruffy-meets-middle class area of London, where it still had that mix of the different types of people which was one of the things I really liked about it. Was living in this house and it kind of backed on, so you could see all these other gardens and houses and things, you heard lots of funny things going on around you. So Robert Granger, her neighbour, is really based on this boy that was my neighbour and I heard him every day calling over the wall to this girl next door and trying to get here to notice him and engage in his very boring conversation. He was one of those very loud children, they can’t talk in any other volume than top volume. It was just funny, and so then I started to picture how I was living in North London, and it was helpful, I sort of needed to know where she lived, and there were certain things I guess I need to picture while I am writing them, otherwise I can’t imagine how does she go to the shop, how does she go to the ?, what can she do on her own? I’ve probably shifted her now, from where she lived to somewhere else which in truth is a lot more chi-chi than it should be, but I can imagine the place and the streets and everything, but maybe if it was ten years ago. That’s the kind of demographic you’d have, it would be a much more Claricey land, not so posh. The problem is in London most of the central London is quite posh now, you have to have quite a lot of money. So I always imagine if people go, well Clarice Bean’s family must be quite posh, they have such a big house, and I said, well, you can have bought your house a long time ago…

It could be Granddad’s house…

Exactly. And I don’t actually think they necessarily are. They do seem to be middle class, but I don’t think they’re especially well off.

Well, to me, there’s enough gaps in the information you give, that you can fill that in any way that makes sense to you. There was a bit about their cranky next-door neighbour, I’ve forgotten her name, complaining about the dogs through the walls, and I thought, oh, it’s a semi. So you get a picture in your head, and you leave it open enough for that.

Exactly, and her dad, I’ve always felt, we don’t really know what his business is. I don’t think he works in such a posh office. That’s her imagination.

Well, the world of grown ups and offices is very exotic, isn’t it. Would you go back to illustrate someone else’s writing?

Yes, if I loved it enough.

I haven’t seen Dan’s Angel, I’d like to hunt that down and have a look at it. But that was kind of a different project…

Yes, that was I took on ages ago, really a long time ago I signed that contract and it just didn’t seem as if it would ever happen, and then finally it suddenly did and it was quite interesting to do. The work was in black and white, for other people, I’ve not done colour. And it was quite a problematic book, in that your really, the star of the book really is the actual paintings. So I did it very very flat on computer, and it was a sort of experiment of doing everything on computer, so I’d draw, and then everything would be scanned in, which is completely different to how I’d usually work. It was kind of interesting, seeing if it would work. I was pleased in that the paintings do stand out. I thought, if I work like I work in Clarice, it would get too muddly, there’d be too many things going on. But I would illustrate for somebody else again, but I would have to really feel I got the text, because I don’t think I’m a natural at it. I think that so much of the time I spend writing is also spent thinking about the image and you’re kind of mulling it over all those months that you’re writing, and when you’re handed a text by another author you don’t have all that time. I don’t really necessarily know where they’re coming from, and I think that some people are truly brilliant at taking someone else’s work ad putting a spin on it that maybe the author didn’t realise was there, and in a good way, not missing the point, not being lazy about it, but someone like Quentin Blake or Edward Gorey, they add so much to text and I think that’s a special skill. Don’t know if I have it.

You’ve said you want to be more ambitious with your books for Penguin. In what way ambitious?

I think what would be really interesting for me, because it was a bit of a risk to take on a third publisher, and my agent and I thought about it very hard, but I loved working with Francesca Dow so much on these Clarice books…

Was she at Orchard?

She was the one who signed me up for Clarice and she moved to Puffin coming up for two years ago. It seemed awful not to work with Francesca again, we did seem to get on so well. So what I decided was, because I’ve got the Clarice and the Charlie and Lola’s and the odd one like That Pesky Rat, that all seem to have a very strong house style, I feel, so if I continue doing them for Orchard. Then at Hodder I was doing, in a way when I look at them, I’m just about to start another one, and they’re all kind of boy characters so far, and they’re narrated, they’re different, to not have that first person voice, they look different to me, anyway, they’re more… they’re less stylised, I think. So they have a particular kind of thing going on. So with Puffin I felt what would be really nice is to maybe not have a house style at all, so that we can do whatever we like. So there’ll be one book which will be, maybe, one that we’re thinking of, maybe will read much more like a comic book in a way, perhaps. And then I’m doing a book with somebody else, in fact, I’m working with someone else on this next one that will be part illustration and part photography. I’m really looking forward to that, because that’ll a whole different kind of book. So that’s sort of the idea really, and also because perhaps maybe Puffin, because they’re such a big company, they are able to do more with paper engineering, or extra pages that you can use, things that perhaps someone else can’t afford to take those risks.

Well, of course, you did The Dream Bed.

Exactly, but I know from doing that how hard it is for them because you’re there every single thing is — and Hodder are a very successful company, but every single thing is however many pence it’s going to cost them, so you’re all thinking about that all the time. It’s not that Puffin have limitless money, but I think that they can, perhaps we can take a bigger risk with something.

And finally, do you go to schools very much, do you get much direct feedback from kids and what sort of feedback do you get from them?

I’ve done quite a lot of school visits now, and I get quite a lot of letters from them, which is really interesting. I think particularly with the Clarice novel, that seemed to change things a lot, because although I’ve had letters before, this was from a slightly different age group, where on their own initiative they decided to write and ask questions or tell me what they liked, or what they thought I should do differently. And it’s really nice, too.

What do they like?

They like Ruby Redfort, which is really interesting. I’ve had stacks of letters.

She is such an interesting creation! I’m reading Trixie Belden, I’m reading, you know, as I’m reading Ruby Redfort, a whole— reading it in bed last night for the second time, I can’t remember them now, but I kept thinking, of there’s a bit of that and a bit of that and a bit of that… you do seem to take things from lots of different…

Yes, well, originally she was — I started writing Ruby Redfort pieces just so I knew what Clarice was reading, not because I was really include so much of it. I was going to have little tiny pieces and then I got really into it. I remembered my sister reading all the Nancy Drew books and how crazy she got about all that, reading series books, and especially because that’s come back as a real fashion, hasn’t it, series books, and so I wanted to be able to talk about that with children as well, without always having to talk about Harry Potter. It’s great that they’ve done that, but there are other books, and I thought it’d be really nice to bring it back to those girl detective type of things.

Donna Parker, that’s who I was thinking of. Did you ever read the Donna Parker books?

No.

She was a teenager, so she wasn’t a detective, but same sort of feel as all of that, and as you’ve said elsewhere, 60s and 70s kid’s television. I was also interested, visually, do you ever get inspiration from — you’ve said you’re a collector, and that seems really evident from the fabrics and nicky-nackys — do you ever get inspired for something in a story by that, or do you start with the story and then go to find your references.

I think it happens all at once, although no illustrating is done before I’ve written the story, really, but I might make little visual notes. But, yeah, it can be anything you know. I mean, I’ve loved looking out of this window. I’ve always been fascinated by tower blocks and things. All those windows, and they just make interesting patterns. And it’s all — things like that, going into a shop, there being — I’ve always been interested in furniture and fabrics and things, so you can just see something that you think well, that makes such a visual thing, and it maybe clicks, or the idea for a particular character who would live with those kind of things. It’s funny, but yeah — or going into a restaurant that you think, it gives that amazing feeling when you walk into a particular place and you think, oh, I’d like to live in this kind of world all the time, so you just work that into a story, so it gives you that good feeling about something.